This is from Rogue Chiefs:

THE surge in the number of African students in China is remarkable. In less than 15 years the African student body has grown 26-fold – from just under 2,000 in 2003 to almost 50,000 in 2015.

THE surge in the number of African students in China is remarkable. In less than 15 years the African student body has grown 26-fold – from just under 2,000 in 2003 to almost 50,000 in 2015.

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the US and UK host around 40,000 African students a year. China surpassed this number in 2014, making it the second most popular destination for African students studying abroad, after France which hosts just over 95,000 students.

And it looks like soon Africans will comprise the biggest proportion of foreign students in China:

Chinese universities are filled with international students from around the world, including Asia, the Americas, Europe and Oceania. The proportion of Asian international students still dwarfs the number of Africans, who make up 13% of the student body. But this number, which is up from 2% in 2003, is growing every year, and much faster than other regions. Proportionally more African students are coming to China each year than students from anywhere else in the world.

Also, African students in China are mostly studying mandarin and engineering:

Based on several surveys, most students tend to be enrolled in Chinese-language courses or engineering degrees. The preference for engineering may be due to the fact that many engineering programmes offered by Chinese universities for international students are taught in English.

And they are more likely than their counterparts in the West to go back home after finishing their studies.

Due to Chinese visa rules, most international students cannot stay in China after their education is complete. This prevents brain-drain and means that China is educating a generation of African students who – unlike their counterparts in France, the US or UK – are more likely to return home and bring their new education and skills with them.

Perhaps the much-discussed skills transfer (or lack thereof) from China to African states will take place at Chinese universities instead of construction sites on the Continent.

The recent decline in the number of foreign students applying to U.S. colleges and universities will no doubt reinforce China’s future soft power advantage over the U.S. in Africa.

What does this mean for research in Africa? According to The Times Higher Education:

China’s investment in Africa is having a positive impact on research, citing China’s African Talents programme. Running from 2012 to 2015, the programme trained 30,000 Africans in various sectors and also funded research equipment and paid for Africans to undertake postdoctoral research in China.

China’s investment in Africa is having a positive impact on research, citing China’s African Talents programme. Running from 2012 to 2015, the programme trained 30,000 Africans in various sectors and also funded research equipment and paid for Africans to undertake postdoctoral research in China.

…. the 20+20 higher education collaboration between China and Africa as a key development in recent years. Launched in 2009, the initiative links 20 universities in Africa with counterparts in China.

And oh, the Indian government is also interested in meeting the demand for higher education in Africa.

In December 2015, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi also announced that the country would offer 50,000 scholarships for Africans over the next five years.

Notice that all this is only partially a result of official Chinese (or Indian) policy. The fact of the matter is that the demand for higher education in Africa has risen at a dizzying pace over the last decade (thanks to increased enrollments since 2000). To the extent that there aren’t enough universities on the Continent to absorb these students, they will invariably keep looking elsewhere.

According to the Economist:

Opening new public institutions to meet growing demand has not been problem-free, either. In 2000 Ethiopia had two public universities; by 2015 it had 29. “These are not universities, they’re shells,” says Paul O’Keefe, a researcher who has interviewed many Ethiopian academics, and heard stories of overcrowded classrooms, lecturers who have nothing more than undergraduate degrees themselves and government spies on campus.

In those countries where higher education was liberalised after the cold war, private universities and colleges, often religious, have sprung up. Between 1990 and 2007 their number soared from 24 to more than 460 (the number of public universities meanwhile doubled to 200).

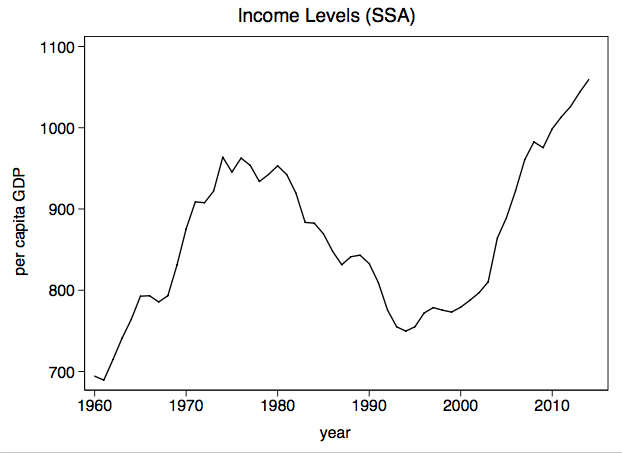

And on a completely random note, the black line on the graph above may explain the otherwise inexplicable persistence of the CFA zone in francophone Africa.

“With a metro, an international firm will often just parachute in its own system,” says Kost. “Bus rapid transit allows existing stakeholders to get involved. That’s what we did in Dar es Salaam and what we’re planning in Nairobi, where the bus bodies will be built in the city and local operators will look after tickets, fare collection and IT. It’s good for the development of the local economy.”

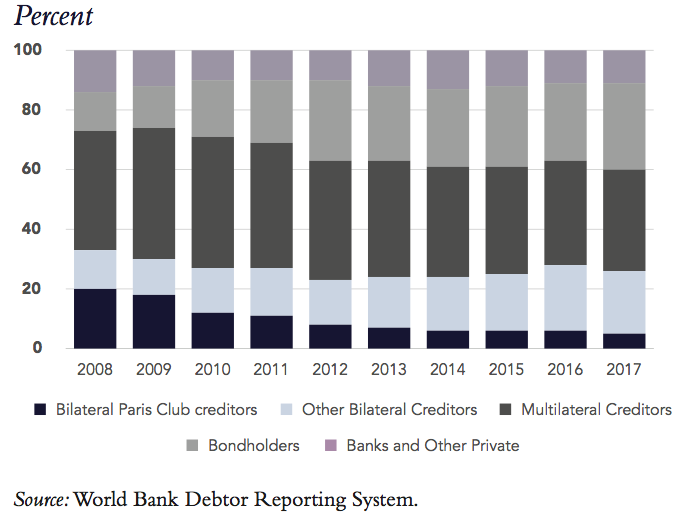

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa accumulated external debt at a faster pace than low- and middle- income countries in other regions in 2017: the combined external debt stock rose 15.5 percent from the previous year to $535 billion. Much of this increase was driven by a sharp rise in borrowing by two of the region’s largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, where the external debt stock rose 29 percent and 21 percent respectively.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa accumulated external debt at a faster pace than low- and middle- income countries in other regions in 2017: the combined external debt stock rose 15.5 percent from the previous year to $535 billion. Much of this increase was driven by a sharp rise in borrowing by two of the region’s largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, where the external debt stock rose 29 percent and 21 percent respectively.

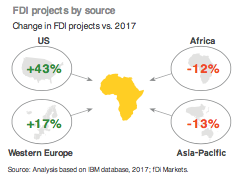

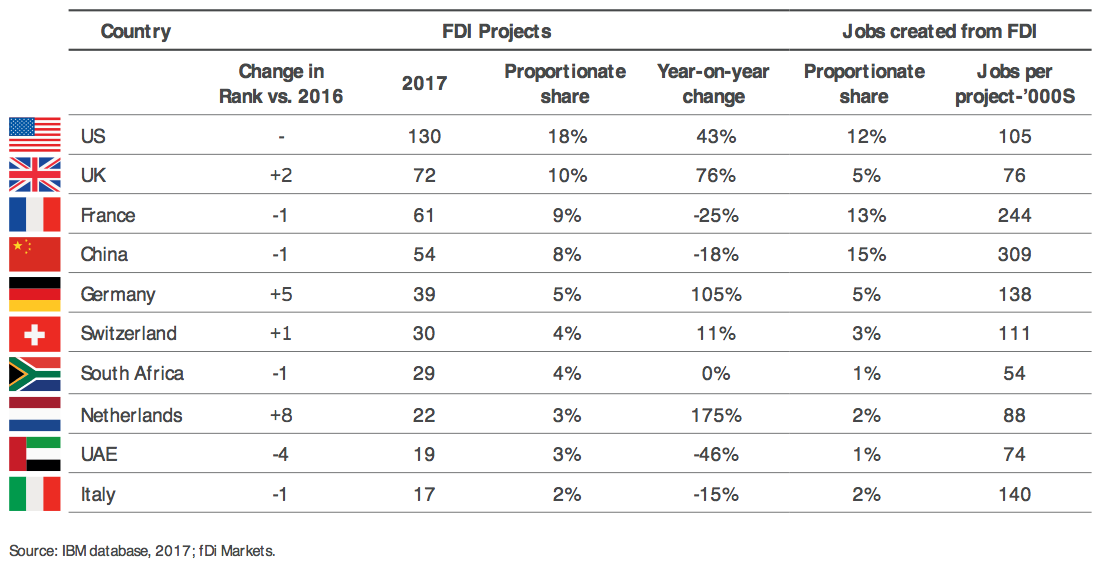

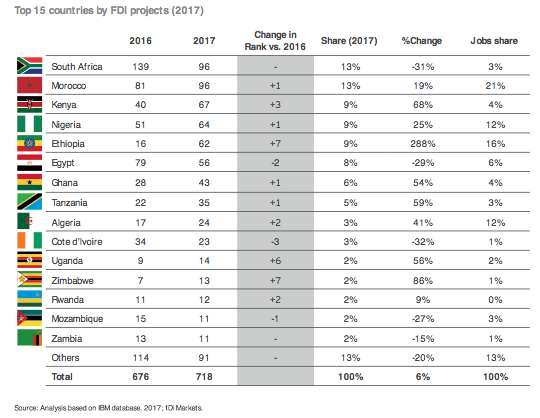

Mature market investors continue building on their deep-seated ties to Africa. In 2017, the US remained the largest investor in the continent, with a noticeable 43% growth in FDI projects. Western Europe, another well-established investor, also built on its already strong investments into Africa, up by 17%. However, emerging-market investments fell, with both intra-regional and Asia-Pacific investment declining by 12% and 13%, respectively. This is, in part, attributable to slower emerging markets growth and weak commodity prices.

Mature market investors continue building on their deep-seated ties to Africa. In 2017, the US remained the largest investor in the continent, with a noticeable 43% growth in FDI projects. Western Europe, another well-established investor, also built on its already strong investments into Africa, up by 17%. However, emerging-market investments fell, with both intra-regional and Asia-Pacific investment declining by 12% and 13%, respectively. This is, in part, attributable to slower emerging markets growth and weak commodity prices.

…. In a display of unexpected warmth, Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s new prime minister, embraced Issaias Afwerki, the ageing Eritrean dictator. In the Eritrean capital, Asmara, which no Ethiopian leader had visited since the war, the two pledged to normalise relations, putting an end to one of Africa’s most bitter conflicts. “There is no border between Ethiopia and Eritrea,” Mr Abiy declared in a televised address. “Instead we have built a bridge of love.”

…. In a display of unexpected warmth, Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s new prime minister, embraced Issaias Afwerki, the ageing Eritrean dictator. In the Eritrean capital, Asmara, which no Ethiopian leader had visited since the war, the two pledged to normalise relations, putting an end to one of Africa’s most bitter conflicts. “There is no border between Ethiopia and Eritrea,” Mr Abiy declared in a televised address. “Instead we have built a bridge of love.” Why Abiy and why now? It is certainly still early days, but I think he might be a case of a lucky draw at a critical time. In the face of

Why Abiy and why now? It is certainly still early days, but I think he might be a case of a lucky draw at a critical time. In the face of

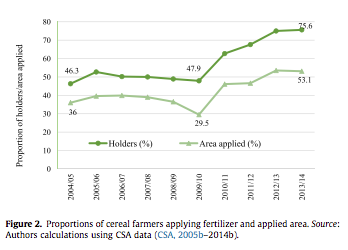

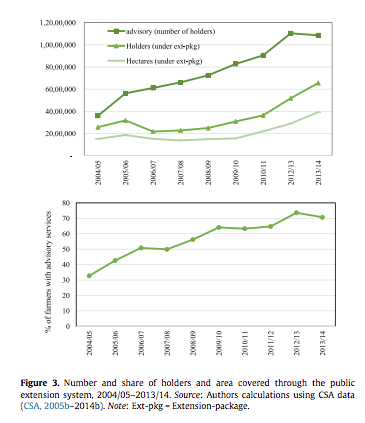

Despite significant efforts, Africa has struggled to imitate the rapid agricultural growth that took place in Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. As a rare but important exception, Ethiopia’s agriculture sector recorded remarkable rapid growth during 2004–14. This paper explores this rapid change in the agriculture sector of this important country – the second most populous in Africa. We review the evidence on agricultural growth and decompose the contributions of modern inputs to growth using an adjusted Solow decomposition model.

Despite significant efforts, Africa has struggled to imitate the rapid agricultural growth that took place in Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. As a rare but important exception, Ethiopia’s agriculture sector recorded remarkable rapid growth during 2004–14. This paper explores this rapid change in the agriculture sector of this important country – the second most populous in Africa. We review the evidence on agricultural growth and decompose the contributions of modern inputs to growth using an adjusted Solow decomposition model. We also highlight the key pathways Ethiopia followed to achieve its agricultural growth. We find that land and labor use expanded significantly and total factor productivity grew by about 2.3% per year over the study period. Moreover, modern input use more than doubled, explaining some of this growth. The expansion in modern input use appears to have been driven by high government expenditures on the agriculture sector, including agricultural extension, but also by an improved road network, higher rural education levels, and favorable international and local price incentives.

We also highlight the key pathways Ethiopia followed to achieve its agricultural growth. We find that land and labor use expanded significantly and total factor productivity grew by about 2.3% per year over the study period. Moreover, modern input use more than doubled, explaining some of this growth. The expansion in modern input use appears to have been driven by high government expenditures on the agriculture sector, including agricultural extension, but also by an improved road network, higher rural education levels, and favorable international and local price incentives.

THE surge in the number of African students in China is remarkable. In less than 15 years the African student body has grown 26-fold – from just under

THE surge in the number of African students in China is remarkable. In less than 15 years the African student body has grown 26-fold – from just under  China’s investment in Africa is having a positive impact on research, citing China’s

China’s investment in Africa is having a positive impact on research, citing China’s