It’s has been illuminating watching African governments respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Here are some lessons I have gleaned from their responses. For those interested, the IMF has a neat summary of county-level policy responses.

[1] We need a lot more descriptive studies of African economies:

COVID-19 was slow to spread in African states (a reminder of the Continent’s isolating from global transportation networks. The first concentrated cases were in Egypt, largely among tourists on Nile cruises). But once cases started appearing across the Continent, governments rushed to implement policies that were eerily similar to those being implemented in wealthier economies. Complete lockdowns, tax breaks, business loans, and interest rate cuts were first to be announced. Cash transfers followed, but even then from the standard purely humanitarian perspective and not as part of a well-thought out, politically-grounded and sustainable policy response. Forget that African economies are (1) largely agrarian and rural; and (2) highly “informal” (i.e. under-served and under-regulated). How do you implement a lockdown when 80% of your labor force is dependent on daily earnings and cannot stock up on food for days? And how do you tell people “wash hands regularly” when the vast majority of your population lacks access to reliable running water? Do African states have the capacity to sustainably deliver cash transfers to needy households throughout this crisis?

In short, African states’ policy responses to the pandemic so far are an urgent reminder of the enormous gaps that exist between knowledge production, policymaking, and objective realities in the region. Now more than ever, there is a need for socially and politically relevant knowledge production. To bridge these gaps, African governments should invest in making their economies more legible. Such investments should target better data collection as well as the establishment of strong academic departments with expertise in political economy and economic history, in addition to other economics subfields. There is absolutely no way around this.

For instance, what do we know about recovery patterns after recessions in different African countries? How will the current shutdown impact rural livelihoods? African states cannot afford to continue making policy from positions of ignorance, or to outsource economic thinking and policymaking. Collect the data. Analyze the data. Have the results inform policy.

Such efforts will go a long way in helping craft domestic narratives and counter-narratives of socio-economic transformation, and hopefully entrench reality-based policymaking, in addition to putting an end to ahistorical and apolitical policymaking. Policymakers must understand that their economies are not simply Denmark waiting to happen.

[2] African governments should strengthen their policy transmission mechanisms:

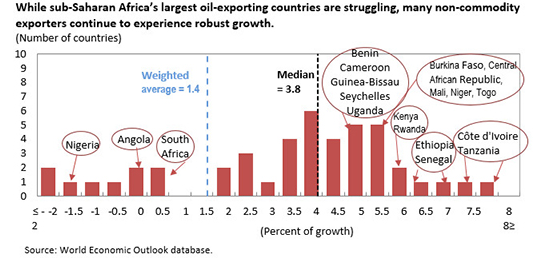

One of biggest mistakes in the history of economic thought was the invention of the notion of “formal” and “informal” economic sectors. This arbitrary distinction continues to blind African policymakers, and limits their abilities to craft transformative policies. In most African countries, governments fixate on minuscule “formal” sectors, and spend billions of dollars attracting mythical foreign investors to create “formal” sector jobs (and in the process subsidize transfer pricing and the creation of very costly enclave economies). Meanwhile, the same governments ignore “informal” and agricultural sectors, despite the fact that in most countries they typically account for significant shares of output (see images) and upwards of 80% of the labor force.

The failure to adequately serve and regulate “informal” and agricultural sectors leaves African policymakers with a set of very blunt tools when it comes to these sectors. How will African governments ensure that SMEs are not completely wiped out by this crisis? How will farm-to-market systems weather the logistical problems caused by large-scale shutdowns? What will be the impact on food prices?

It makes little sense to lower SME taxes or incentivize bank lending to SMEs if the vast majority of SMEs neither pay taxes nor borrow from banks. “Informal” sector workers are typically also not plugged into any skeletal social safety nets that may exist, such as health insurance or pension schemes.

For example, “[i]n Senegal one 2016 government/Millennium Challenge Corporation study found [that] only 15 companies pay up to 75% of the state’s tax revenue.”

Moving forward, African countries need to jettison the “formal” vs “informal” sectors distinction. As the primary source of employment, the “informal” and agricultural sectors deserve a lot more public investments targeted at both broader market creation (domestic and international) and productivity increases. Such investments would give governments important policy levers during both good and bad times.

The fact of the matter is that agriculture and SMEs are the mainstays of African economies. It is about time that African states’ economic policies and budgeting reflected that reality. Failure to do so will continue to severely limit the efficacy of policy interventions, and leave governments wasting scarce resources attracting investments with very little multiplier effects in their economies.

[3] Elite complacency in Africa is about to get a lot more expensive:

One need not be wearing a tinfoil hat to see the many ways in which African leaders continue to act like colonial “Native Administrators”. Some do not even pretend to care about aspiring to govern well-ordered societies. For almost six decades the global state system has accommodated elite mediocrity in Africa. During this period, the collusion between African and non-African elites in the pilfering of the region’s resources was balanced with aid money and other forms of support.

That is changing. Western elites and publics have began to question the utility of foreign aid. Forgetting that the aid is what buys elite-level African alliances, they have come to expect loyalty from African states as a pre-ordained birthright. Many Western countries have also seen significant deterioration in the quality of their political leadership in the recent past, thereby exposing them to a range of domestic crises that will likely distract them into the medium term. China, the other major global player, is not ready to step into the void.

And so African elites will be forced to step up. What do you do when, after decades of presiding over abominable public health systems that are totally dependent on the generosity of foreigners, you cannot get on a plane to seek medical care abroad? And how do you deal with a pandemic that hits the entire globe at once?

It is no secret that the Global Public Health architecture was built to police and contain disease outbreaks in low-income countries. This has allowed African governments to routinely globalize their public health emergencies and therefore get away with poor governance and lack of dependable healthcare systems.

The combination of an inward orientation of the “international community” and likely recurrence of truly global pandemics will mean that African states will have to build robust and sustainable domestic healthcare systems. It will no longer be a given that the American CDC or the WHO will swoop in with solutions. Under these conditions, failure to plan will likely lead to mass deaths in African states.

[4] African progressivism needs a reset:

As Toby Green documents in A Fistful of Shells, modern African progressivism (defined as working towards broad-based transformative change) has a long history — going back to the 18th century. Men like Usman dan Fodio reacted to what they perceived to be elite complacency and moral depravity by organizing and seizing power. However, it is fair to say that the postcolonial variant of progressivism in the region has run out of steam. In nearly every country, it has become permanently oppositionist and anti-establishment. Life out of power has infused it with a streak of expressive performativity that is increasingly divorced from the political and economic realities in the region, and sorely lacking in intellectual rigor (there are exceptions, of course). Arguably, the Thomas Sankara administration (with warts and all) was the last truly progressive administration in the region.

It is about time that African progressivism focused not just on criticizing those in power, but also on developing viable political programs that can win power. This will require organization, political education and communication that resonates with mass publics, genuine openness to knowing “the realities on the ground”, and a dose of

principled ideological promiscuitypragmatism. The habit of waiting for perfectly enlightened voters and politicians under perfect institutional conditions effectively concedes the fight to the region’s shamelessly inept water-carriers.After 60 years in power, Africa’s ruling elites have become perhaps the most complacent lot in the world. Their destruction of higher education and the region’s intelligentsia in the 1970s allowed them to limit the role of ideas in politics and policymaking. It also helped that they found willing “apolitical” development partners in the “international community.” Even the most “progressive” among them care more about their countries’ rankings in the World Bank’s “Doing Business Index” than in the state of their “informal” and agricultural sectors.

It is time to infuse African leadership with new thinking and moral foundations of social contracts. Only then will the region’s states be in a position to build the necessary resilience to weather emergencies like COVID-19, and provide necessary conditions for Africans to thrive at home and abroad.

In the year 2000, Ugandan exports to Rwanda were worth $9 million. By the 2017/2018 financial year, this figure had shot up to $197 million, against imports of $20 million, giving it a surplus of $177 million, despite the icy relations currently prevailing.

In the year 2000, Ugandan exports to Rwanda were worth $9 million. By the 2017/2018 financial year, this figure had shot up to $197 million, against imports of $20 million, giving it a surplus of $177 million, despite the icy relations currently prevailing.