Dear readers,

I am blogging again! This time on Substack. Go over and subscribe to receive new posts every week!

Thank you for reading this blog over the years and looking forward to reconnecting again.

Ken

Dear readers,

I am blogging again! This time on Substack. Go over and subscribe to receive new posts every week!

Thank you for reading this blog over the years and looking forward to reconnecting again.

Ken

The battle over the waters of the Blue Nile, pitting Ethiopia against Egypt and Sudan, has been all over the news lately. Notably, the debate has focused on the Blue Nile and largely ignored the other Nile, the White Nile. Which is odd because most accounts of the “source of the Nile” and official measures of the river’s length focus on the White Nile. More importantly, any lasting diplomatic solution to the ongoing inter-state contests over Nile waters will necessarily have to include all the Nile basin states — many of which are politically relevant on account of being part of the wider White Nile basin.

The reason for ignoring the White Nile is simple: less than half of its waters actually reach Sudan and Egypt. An estimated 50% of the White Nile’s waters evaporate in the Sudd (a massive swamp whose full extent is about twice the size of Rwanda). Overall, the river contributes about a fifth of the Nile’s total flow. It therefore makes sense that Egypt and Sudan care more about the Blue Nile and Ethiopia’s ongoing construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The reason for ignoring the White Nile is simple: less than half of its waters actually reach Sudan and Egypt. An estimated 50% of the White Nile’s waters evaporate in the Sudd (a massive swamp whose full extent is about twice the size of Rwanda). Overall, the river contributes about a fifth of the Nile’s total flow. It therefore makes sense that Egypt and Sudan care more about the Blue Nile and Ethiopia’s ongoing construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Yet the While Nile has not always been ignored. Multiple times over the last century, the loss of water to evaporation in the Sudd generated debates about how to ensure that more of the rivers’ waters reached Egypt. Potential solutions included damming upstream lakes (Albert, Kyoga, Victoria) to act as reservoirs and reduce water loss to evaporation, dredging parts of the Sudd to increase the rate of flow, and building earth banks to prevent overflow into the wetlands.

However, the one idea that actually got off the ground was the construction of a canal to bypass the Sudd (see image below).

The first plans to build the Jonglei Canal emerged in the early 1900s under the colonial Anglo-Egyptian condominium in Sudan. After Sudan’s independence in 1956, Egypt convinced Khartoum to build the canal. Construction works started around 1975, with Egypt and Sudan agreeing to jointly shoulder the $300m cost of the project (about $1.44b in 2020 dollars). But then politics and conflict intervened. Following the collapse of the Addis Ababa Agreement and resumption of Sudan’s civil war in 1983, the canal construction sites became easy targets for rebel forces seeking to depose Gaafar Nimeiry’s repressive regime in Khartoum.

The first plans to build the Jonglei Canal emerged in the early 1900s under the colonial Anglo-Egyptian condominium in Sudan. After Sudan’s independence in 1956, Egypt convinced Khartoum to build the canal. Construction works started around 1975, with Egypt and Sudan agreeing to jointly shoulder the $300m cost of the project (about $1.44b in 2020 dollars). But then politics and conflict intervened. Following the collapse of the Addis Ababa Agreement and resumption of Sudan’s civil war in 1983, the canal construction sites became easy targets for rebel forces seeking to depose Gaafar Nimeiry’s repressive regime in Khartoum.

At the time, about two thirds of the 360k Jonglei Canal (which is visible on google maps) had already been excavated. The canal was intended to be about 50m wide on average and between 4-8m deep. For comparison, when completed the Jonglei Canal was going to be longer than the Suez (193km) and Panama (80km) canals combined.

Proponents of the project argued that it would provide effective flood control, boost agricultural development, improve riparian navigation between Bor and Malakal, and free up of more water to flow downstream the Nile. Critics of the project have often highlighted the likely reduction in fishing resources, exacerbation of competition for grazing areas among communities that rely on the region’s grasslands, likely aridification of the central South Sudanese region due to reduced rainfall, risk of ecological damage (the Sudd has a rich flora and fauna), and disruption of vital wildlife migration routes.

Various models suggest that the construction of the canal would decrease the size of the Sudd by up to 32%. The figure could be higher (up to 50%), especially as upstream Nile basin counties build their own dams and expand their use of water for irrigation (other scholars have placed likely peak contraction of the Sudd at 16%). While it is possible to regulate the flow into the canal to mitigate extreme aridification of the Sudd wetlands, the fact that such decisions would be at the discretion of politicians pose real environmental risks.

As tensions rose over Ethiopia’s GERD, some commentators suggested that the Jonglei canal may provide a way out of the impasse. But authorities in South Sudan remain opposed to the project. In addition to the hard-to-predict environmental impacts of the canal, Juba is rightfully worried that a piece of international infrastructure of this kind would likely turn South Sudan into a geopolitical pawn. Most reasonable people would agree that Juba is in no position to enter into a fair agreement with its neighbors to the north. That said, it is not inconceivable that as Ethiopia uses ever more of the Blue Nile’s waters, Egypt and Sudan might be forced to give South Sudan a better deal to complete construction of the Jonglei Canal. And it goes without saying that the success of such a deal would be predicated on support from the other Nile basin states.

This is from Isma’il Kushkush writing in the Smithsonian Magazine:

If you drive north from Khartoum along a narrow desert road toward the ancient city of Meroe, a breathtaking view emerges from beyond the mirage: dozens of steep pyramids piercing the horizon. No matter how many times you may visit, there is an awed sense of discovery. In Meroe itself, once the capital of the Kingdom of Kush, the road divides the city. To the east is the royal cemetery, packed with close to 50 sandstone and red brick pyramids of varying heights; many have broken tops, the legacy of 19th-century European looters. To the west is the royal city, which includes the ruins of a palace, a temple and a royal bath. Each structure has distinctive architecture that draws on local, Egyptian and Greco-Roman decorative tastes—evidence of Meroe’s global connections.

Off the highway, men wearing Sudanese jalabiyas and turbans ride camels across the desert sands. Although the area is largely free of the trappings of modern tourism, a few local merchants on straw mats in the sand sell small clay replicas of the pyramids. As you approach the royal cemetery on foot, climbing large, rippled dunes, Meroe’s pyramids, lined neatly in rows, rise as high as 100 feet toward the sky. “It’s like opening a fairytale book,” a friend once said to me.

And it only gets better and better. Read the whole thing here.

Here’s a description:

The ISIS Files provide a unique cross-sectional snapshot of life in Mosul under the Islamic State, spanning doctrinal guidance from its command to the paperwork of its bureaucracy to the notes of students in its classrooms. The picture that emerges from this repository is revealing in both its range and complexity. On the one hand, documents from the Islamic Police and Agriculture departments tell of an organization seemingly obsessed with bureaucracy and institutionalizing every detail of its system of control. On the other, Arendt’s “banality of evil” comes to 6 mind when reading the paperwork of its real estate and zakat (alms tax for the poor) offices, or the bored scribblings of da’wa (proselytization) and military students in the Islamic State’s classrooms (emphasis added). By understanding The ISIS Files as a snapshot of life under the Islamic State’s control, the publications that will accompany each tranche of primary source materials released on the online repository have an important role to play in establishing their historic and strategic context.

In the 1970s, prominent critics of Kenya’s capitalist economy often characterized the country as a land of 10 millionaires and 10 million beggars. Many also (implicitly) compared Kenya to Tanzania. Back then, Tanzania was in the midst of implementing Ujamaa under President Julius Nyerere. The trope of Kenya being a highly unequal “dog-eat-dog society,” and Tanzania being less unequal stuck, and persists to this day.

But the data tell a different story. According to the Knight Frank Wealth Report, Tanzania has the fifth largest number of high networth individuals in Africa ($30m and more), ahead of Kenya:

South Africa led the pack with 1,033 ultra-rich persons followed by Egypt (764) Nigeria (724) Morocco (215) and Tanzania (114)

Kenya is 6th, with only 42 individuals worth more than $30m.

Kenya has a Gini index of 40.8 (2015) and Tanzania 40.5 (2017).

I continue to struggle with fiction, with quite a few unfinished. Suggestions on how to win this battle are welcome.

This is from a CGD paper by Scott Morris, Brad Parks, and Alysha Gardner:

The World Bank’s portfolio is more concessional than China’s portfolio in every region of the world, and sometimes dramatically so. The overall concessionality of China’s portfolio demonstrates less variation from region-to-region, hovering between 15%-22% in all regions except Europe and Latin America. By contrast, the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio varies widely — from a low of 15% in Latin America to a high of 60% in Sub-Saharan Africa (which is also the region where Chinese lending volumes are highest). The differences between China and the World Bank are most stark in Sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio in Sub-Saharan Africa is nearly 60%, China’s portfolio concessionality in the same region is only 22.5% All three measures of lending terms contribute to these differences in portfolio concessionality rates: China consistently has higher interest rates, shorter maturity lengths, and shorter grace periods

Notice that China is neck and neck with the World Bank across Africa, unlike in other regions where Bank lending dominates. What proportion of Chinese lending in Africa are concessional loans?

Whereas the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio in Sub-Saharan Africa is nearly 60%, China’s portfolio concessionality in the same region is only 22.5% .

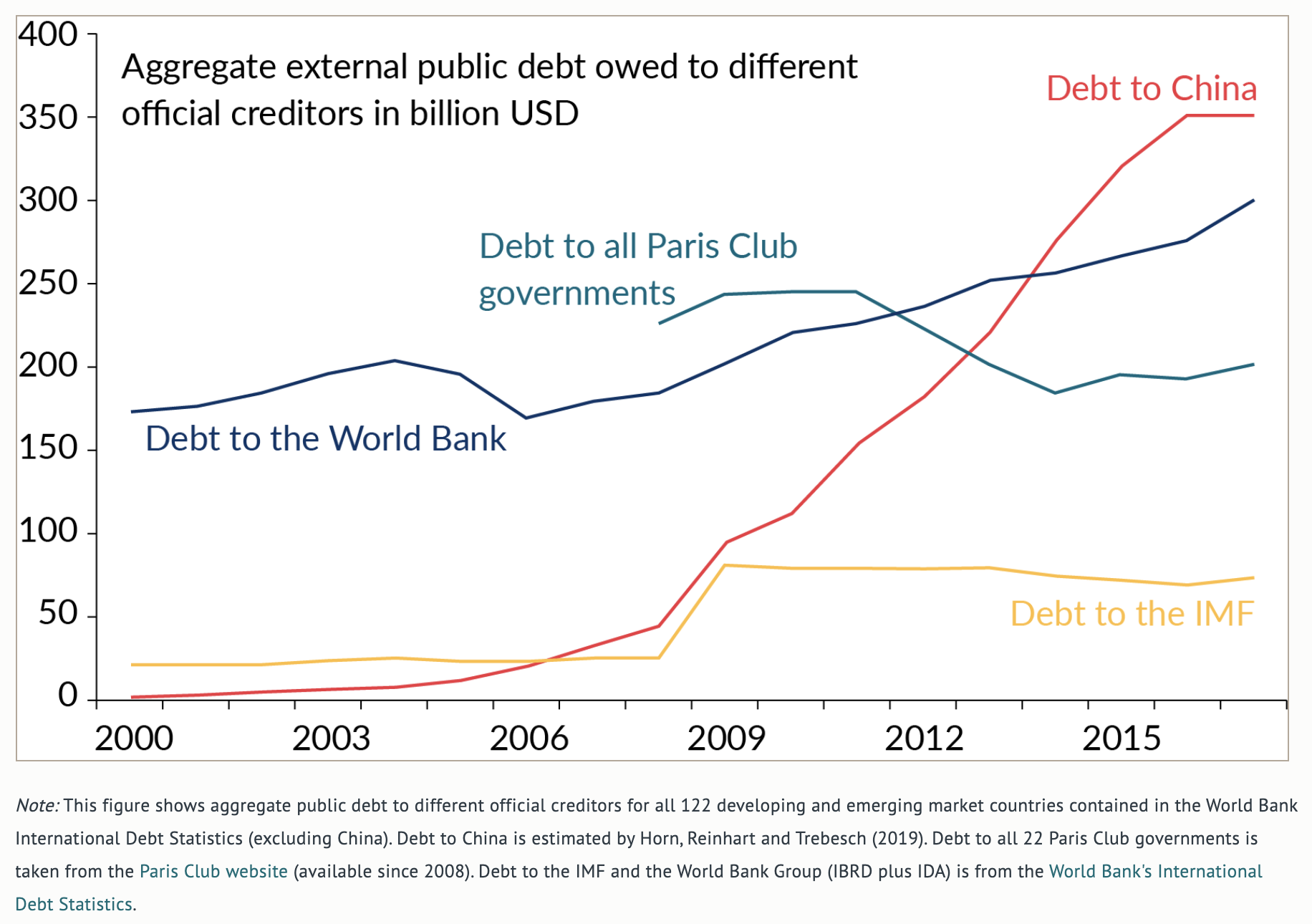

Recall that, overall, China is the single largest creditor to developing countries:

What we should make of African states’ indebtedness to China? A lot of people have opined that China is engaging in debt diplomacy — intentionally trapping African countries with high interest non-concessional loans, after which it will demand all manner of concessions from them (perhaps UN votes, or other forms of assistance in aid of Beijing’s geo-strategic objectives). I have two thoughts on this.

First, the Chinese debt bonanza seen on the Continent over the last two decades was driven, in part, by local demand for infrastructure and other visible and attributable forms of “development.” And yes, intra-elite distributive politics and over-pricing was also involved. And Chinese firms, which often competed against each other, played along, too — perhaps because of the reasons Yuen Yueng Ang describes in her latest book (highly recommended). With this in mind, it is not entirely true to claim that Beijing pushed loans on African states. While it is true that some of the projects were driven more by the quest for kickbacks than for economic reasons, the fact is that individual country dynamics drove the demand for loans and projects. Some of those fit into China’s global geopolitical ambitions (like the Belt and Road Initiative). Others did not.

Second, let’s think through the debt diplomacy game. Is the idea that China would ruin dozens of African states’ fiscal positions so much so that they would turn to Beijing for bailouts? How many Hambantota’s can China run across Africa? Does Beijing have the fiscal, military, or administrative capacity to do so?

The simple fact is that the use of gunboat diplomacy to settle sovereign debts is no longer kosher within the international system. My guess is that while Beijing certainly was out to buy influence with loans and other commercial relations, it also wanted to make money. Chinese officials were not running around peddling cheap concessional loans (see above). They were out looking for business for Chinese firms and banks. And so to the extent that African countries mismanaged their debt or invested in economically unviable infrastructure projects (even if in collusion with Chinese firms), that is on them.

Moving forward, it is clear that it will be in China’s best interest to make sure that its commercial relations in Africa do not stray too far from general economic viability. A strategic coddling of poor and weak allies will be very costly in the long run (see France in the Sahel). It will also likely turn African public opinion against China. For a long time, majorities of African publics have reported net favorable views of China. But this will most likely change if China morphs from a largely likable development partner building roads, power lines, and water works, to little more than a banker of tinpot tyrants in the business of building white elephants and saddling future generations with debt.

This is the abstract of Olsson, Baaz, and Martinsson in the JDE:

In many post-conflict states with a weak fiscal capacity, illicit domestic levies on trade remain a serious obstacle to economic development. In this paper, we explore the interplay between traders and authorities on Congo River – a key transport corridor in one of the world’s poorest and most conflict-ridden countries; DR Congo. We outline a general theoretical framework featuring transport operators who need to pass multiple taxing stations and negotiate over taxes with several authorities on their way to a central market place. We then examine empirically the organization, extent, and factors explaining the level of taxes charged by various authorities across stations, by collecting primary data from boat operators. Most of the de facto taxes charged on Congo River have no explicit support in laws or government regulations and have been characterized as a “fend for yourself”-system of funding. Our study shows that traders have to pass more than 10 stations downstream where about 20 different authorities charge taxes. In line with hold-up theory, we find that the average level of taxation tends to increase downstream closer to Kinshasa, but authorities that were explicitly prohibited from taxing in a recent decree instead extract more payments upstream. Our results illustrate a highly dysfunctional taxing regime that nonetheless is strikingly similar to anecdotal evidence of the situation on the Rhine before 1800. In the long run, a removal of domestic river taxation on Congo River should have the potential to raise trade substantially.

The magnitude of taxation is not trivial:

In our applied analysis, we collect novel data from a sample 137 river boat operators, which corresponds to approximately 90 percent of all boats arriving during our 3.5 month survey period. During the journey downstream on Congo River, a boat passes several administrative stations where various authorities are present. Our data record more than 2000 de facto tax payments to more than 20 different authorities at 10 different stations on the journeys downstream Congo River towards the capital Kinshasa. The average total cost of such de facto taxes amounts to almost 14 percent of the variable costs of a single journey, equivalent to more than 1.5 times the official GDP per capita in DR Congo and 9 times the average monthly wage of a public official.

… In total, 2226 tax payments were recorded among the sampled boats, adding up to a total sum of 76,148 USD. On average, boat operators made about 18 payments per journey.

This is from the Sentry Project, which documents the web of corruption and profiteering among South Sudan’s political/military elite:

There are approximately 700 military figures with the rank of general in South Sudan. Nationally, that’s about

three times as many generals as physicians…..

This report examines the commercial and financial activities of former Army chiefs of staff Gabriel Jok Riak, James Hoth Mai, Paul Malong Awan, and Oyay Deng Ajak, along with senior military officers Salva Mathok Gengdit, Bol Akot Bol, Garang Mabil, and Marial Chanuong. Militia leaders linked to major instances of

violence both before and during the civil war that ended in February 2020—Gathoth Gatkuoth Hothnyang, Johnson Olony, and David Yau Yau—are also profiled here…..

South Sudan’s feuding politicians reached a compromise in February 2020, setting in motion the process of forming the long-awaited transitional government. The political situation remains tenuous as years of conflict have created distrust between leading politicians in the country. As the African Union noted in its investigation of the root causes of the conflict, weakened accountability measures and corruption helped precipitate the country’s descent into civil conflict in December 2013. The 2018 peace agreement contains provisions that call for profound reform of institutions of accountability to curb competitive corruption between senior-level politicians in order to prevent a return to war.

With the transitional government in place, maintaining international pressure will be critical to prevent corruption and elite competition from once again triggering conflict. Much of the legislative framework for combating corruption already exists in South Sudan’s constitution and legal code. For effective implementation and enforcement during the transitional period, and to ensure that lasting peace prevails in South Sudan, international assistance in strengthening capacities and facilitating access to donor funding will be important.

This is absolute gold:

Coastal West Africa and Nigeria, the Great Lakes region, the Ethiopian highlands, the Nile Delta and the Mediterranean coast pack half of Africa’s population.

Source: interesting maps

Africa’s population is projected to keep growing for the next century (see UN projections below), although current projections most certainly overestimate the rate of growth.

The Daily Maverick has an excellent piece on how the ongoing insurgency in northern Mozambique may be reshaping the illicit trade industry in the country:

The most reliable reports of the insurgents developing an illicit income stream are linked to the heroin trade. There is a significant range in street-level heroin prices across East and Southern Africa. The range in prices in northern Mozambique – far greater than found in any other research site – reflects the variance in heroin quality available in Cabo Delgado that we also found during qualitative fieldwork in the region…

There has been a significant recent shift in the rhetoric and style of attacks committed by the Cabo Delgado insurgents. Rather than terrorising communities as in previous months, they are instead attacking state infrastructure and military bases. They have used their increasingly vocal media campaign to declare their intentions to create a caliphate. Analysts we interviewed suggest that part of the insurgents’ aim is to re-establish control over areas historically controlled by Muslim sultanates along the Swahili coast. This historical claim would play into the caliphate narrative and the group’s claim of legitimacy.

If this territorial control were achieved – along the coast from Quissanga to Palma as well as on the key inland transport corridor along the N380 road and the town of Macomia – this could vastly change the dynamics of the insurgency.

Control over key sea and land routes would allow the insurgents to “tax” legal and illicit economies in the region more systematically. While there may already be some protection of heroin trafficking and involvement in the gold and ruby trade, this could expand to include human smuggling, timber trafficking and possibly a share of the illegal wildlife trade.

The insurgents’ access to Mozambique’s illicit trade networks is an ominous development. Taxation of the drug trade and access to point resources like gold will likely boost the insurgents’ staying power and capacity for violence, while also weakening their dependence on local populations. That probably means more civilian deaths.

This is from a new paper by Alicia Barriga and Nathan Fiala in World Development:

Results from the tests showed very high levels of DNA similarity (above 98%) and good performance in general, but highly variable quality in terms of the ability of the seed to germinate under standard conditions. We do not see differences in average outcomes across the distribution levels, though variation in seed performance does increase further down the supply chain.

The results of the tests point to potentially important issues for the quality of seeds. The variation in germination suggests that buying a random bag of seeds in this particular distribution chain can matter a lot for farmer’s production. The high rate of seed similarity suggests that the main concern among policy makers and researchers, that sellers add inert or low-quality material to the seeds, is likely not the case, at least for the maize sector in the districts we study. However, given the remoteness of these districts and the lack of any oversight in these areas, we believe the results are likely a lower bound for the country as a whole.

The supply chain analysis suggests that the quality of seed does not deteriorate along the supply chain. The quality is the same, on average, across all types of suppliers after leaving the breeders. However, we observe high variation of seeds’ performance results on germination, moisture, and vigor, suggesting that results are more consistent with issues of mishandling and poor storage of seeds, possibly related to temperature or quality controls, rather than sellers purposefully adulterating seeds. Variation on these indicators is usually associated with mishandling during transportation and storage.

As the authors note in the paper, African governments and their external donors have put a lot of effort in “certification and labeling so as to reduce the possibility of adulteration by downstream sellers”. Obviously, e-labels and systems of verifying seed authenticity in the fight against adulteration are important. But equally important is an understanding of how the seed distribution system works. And that is one of the major contributions of this paper. Corruption is not always the problem.

Interestingly, Uganda bests both Kenya and Tanzania on productivity in the cereal sector (I made the graph using FAO data). Despite starting off with relatively lower productivity and having gone through civil conflict beginning in the late 1970s, Uganda has since around 2007 clearly separated itself from both Kenya and Tanzania (and appears to have plateaued). Productivity in Kenya peaked in the early 1980s and has pretty much stagnated since. Tanzania’s figures appear to be trending upwards having collapsed in the early 2000s. There is likely an element of soil quality and general aridity involved in these trends. According to the FAO, Kenya and Tanzania use fertilizer at significantly higher rates than Uganda. For comparison, cereal yield in Vietnam is about 2.7 times higher than in Uganda.

Thandekile Moyo has as great piece over at Africa Portal on life after 40 years of independence in Zimbabwe. Ian Smith’s Rhodesia was swept into the dustbin of history on April 18th, 1980. Since then Zimbabwe has gone through a lot, as vividly described by Moyo. Overall, Zimbabwean elites have consistently betrayed the ideals of the Second Chimurenga over the last 40 years.

Who are the “born frees”?

They call those of us born in Zimbabwe and after 1980 “bornfrees”. We are the “lucky” generations, the generations that do not know the heartbreak and terror of war, generations that know nothing about the indignity and injustice of racism, nothing about the brutality of domination and white supremacism and the helplessness of poverty. We know nothing about suffering, we were born free.

On the economy:

Many “bornfrees” in Zimbabwe still live with their parents. Forty-year-old men and women who should by now have built their own homes are stuck at home because we cannot afford to move out. Most Zimbabweans are either unemployed, underemployed or living from hand to mouth. The Government is the biggest employer and pays an average of ZW$2,500/month (USD$70).

On the provision of essential public services:

In spite of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Zimbabwe’s Vice President Constantino Chiwenga flew to China in March because that is where he receives his healthcare. Zimbabwean leaders do not use Zimbabwean hospitals. When then Vice President Mnangagwa was suspected to have been a victim of poisoning at a rally in 2017, he was airlifted to South Africa for treatment. When Vice President Kembo Mohadi fell ill in 2019, he too was flown to South Africa. This is the legacy left by Robert Mugabe who himself eventually died at a hospital in Singapore.

On the Zimbabwean state’s approach to competitive electoral politics:

When Matebeleland resoundingly voted for ZAPU in the 1980 elections the “Black Government” responded by arresting ZAPU leaders and murdering 20,000 of their supporters in a genocide known as Gukurahundi.

Such torture and murder of opposition supporters have continued over the years. Just last year, a comedian, Samantha Kurera was abducted by suspected state agents and tortured for producing skits considered to be anti-government.

What is there to celebrate about Zimbabwean independence?

Zimbabwe turns 40 on 18 April. Growing up, Independence Day was a major deal. With age though, I find myself disoriented and struggling to comprehend what exactly there is to celebrate. What does it mean to be independent? Bornfree?

Free of what? Free from what? Free to do what?

What explains the postcolonial divergence between Kenya and Zimbabwe?