Yesterday at 3 PM four suspected Al Shabaab gunmen attacked the Dusit complex (14 Riverside) in Nairobi. Initial reports indicate that at least 21 people were killed in the attack. More than 700 people were at the complex at the time and were evacuated.

It is worth noting that yesterday was the third anniversary (15/01/2016) of the El Adde attack (also by Al Shabaab) on a Kenyan military base in Somalia. El Adde was the deadliest attack in Kenyan military history — with at least 141 soldiers reportedly killed.

As the Dusit attack was unfolding, media houses began publishing images from the complex. One image — in a New York Times story — drew the ire of Kenyans for showing two dead men slumped over their seats at a cafe. The Times claimed that this was standard policy.

Kenyans did not buy their explanation. And for good reason. At the very least, the image was insensitive. The two men were easily identifiable by their clothing.

First, it’s one thing to show the image of the dead covered in the streets (the ethics of which are also questionable), and another to show two easily-identifiable dead men slumped over their seats at a cafe. It takes a significant amount of empathy gap to not notice this difference. Second, and more importantly, Kenyans’ demands for respect for victims and their families are valid in their own right. They do not need further validation by what the Times does elsewhere. It is not ordained that what passes for Nice or New York ought to naturally pass for Nairobi. As an institution, the Times ought to have shown that it takes the complaints about the image seriously.

Here is a great explainer on why a lot of Kenyans took particular offense to the Times’ response:

… In the New York Times’ initial story about the event, penned by recently appointed East Africa bureau chief Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, the photo editors decided to include an image (from the wire Associated Press) that has since spurred not one but two trending hashtags in Nairobi.

Taken at the popular Secret Garden Café tucked away in the compound, the grainy photograph depicts a scene of utter carnage. Two unidentified men’s lifeless bodies are slumped over on their tables, their laptops still next to them. It is a horrific reminder of the indiscriminate nature of terrorist attacks.

… What particularly angered Kaigwa — and many others — is how de Freytas-Tamura responded to the controversy: she reminded her critics that as the reporter, she did not choose the photo, and that people could take their concerns up directly with the photo department. She was factually correct, but to many Kenyans, she displayed an unnerving callousness.

“I think what that tweet showed to people is that they didn’t have someone who listen[ed] to them and empathize[ed] with them,” says Kaigwa. The reporter later deleted the tweet and instead shared the New York Times’ official policy on showing casualties during terrorist attacks.

Underlying the current discussion (and no doubt fueling the expressions of outrage) is, of course, a long history of the Western press being callous about publishing images of dead Africans. And it is in that context that the reaction from Kenyans should be understood. My hope is that this present discussion will force the Times and other media houses to review their guidelines on publishing images of the dead — regardless of their nationality.

Finally, and to echo Nanjala Nyabola, it goes without saying that the Times’ reprehensible editorial choice in this instance should not be used to attack individual journalists or the freedom of the press more generally.

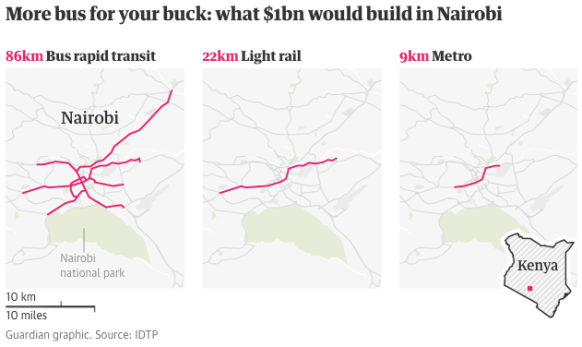

“With a metro, an international firm will often just parachute in its own system,” says Kost. “Bus rapid transit allows existing stakeholders to get involved. That’s what we did in Dar es Salaam and what we’re planning in Nairobi, where the bus bodies will be built in the city and local operators will look after tickets, fare collection and IT. It’s good for the development of the local economy.”

“With a metro, an international firm will often just parachute in its own system,” says Kost. “Bus rapid transit allows existing stakeholders to get involved. That’s what we did in Dar es Salaam and what we’re planning in Nairobi, where the bus bodies will be built in the city and local operators will look after tickets, fare collection and IT. It’s good for the development of the local economy.”

The Congolese government, however, has shown little interest in ending peripheral wars that do not threaten its survival. This does not make it less rational: it has privileged maintaining patronage networks—some of which incorporate its opponents—over the security of its citizens, and elite survival over institutional reform. Overall, these logics have emerged incrementally as various peace deals and integration efforts created deeply factionalized security services. Kinshasa then decided to use that as a means to distribute patronage and reward loyalty, instead of instilling discipline and monopolizing violence through reform, which could create a backlash within the senior officer corps.

The Congolese government, however, has shown little interest in ending peripheral wars that do not threaten its survival. This does not make it less rational: it has privileged maintaining patronage networks—some of which incorporate its opponents—over the security of its citizens, and elite survival over institutional reform. Overall, these logics have emerged incrementally as various peace deals and integration efforts created deeply factionalized security services. Kinshasa then decided to use that as a means to distribute patronage and reward loyalty, instead of instilling discipline and monopolizing violence through reform, which could create a backlash within the senior officer corps.

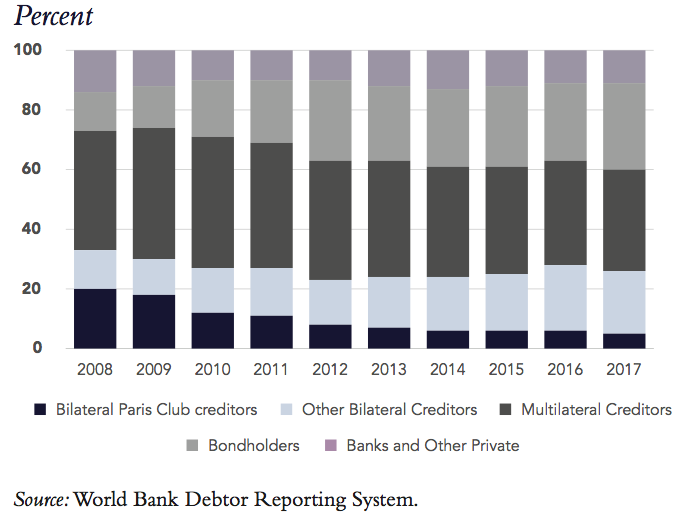

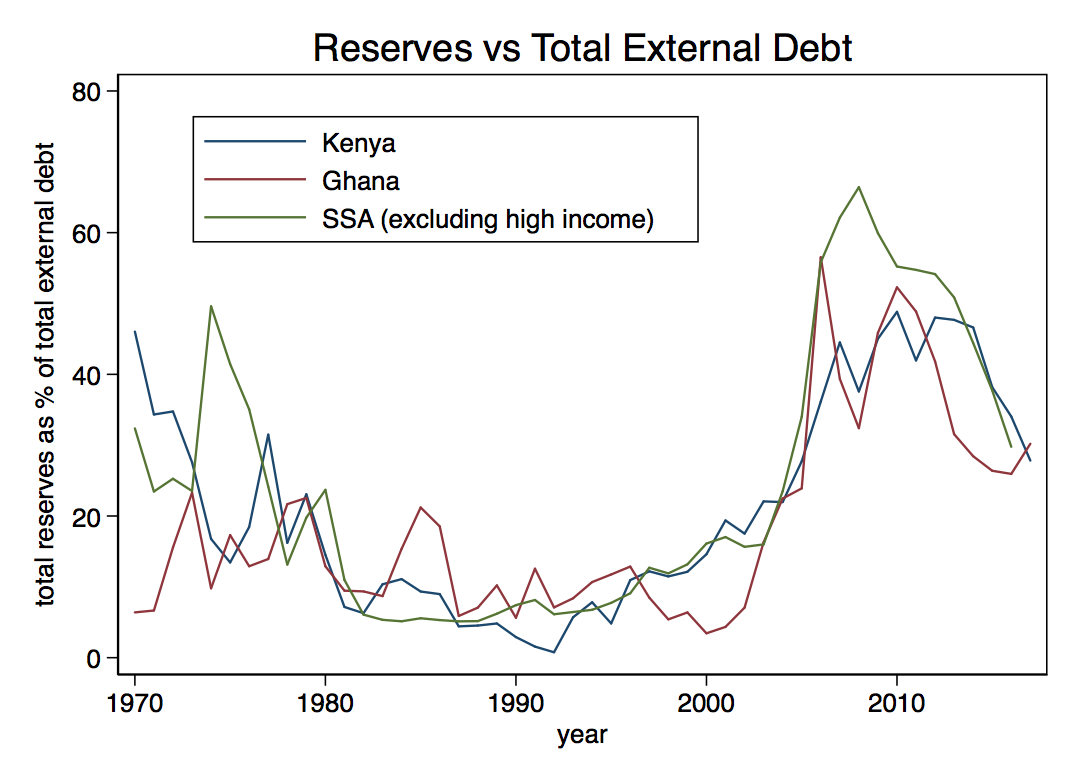

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa accumulated external debt at a faster pace than low- and middle- income countries in other regions in 2017: the combined external debt stock rose 15.5 percent from the previous year to $535 billion. Much of this increase was driven by a sharp rise in borrowing by two of the region’s largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, where the external debt stock rose 29 percent and 21 percent respectively.

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa accumulated external debt at a faster pace than low- and middle- income countries in other regions in 2017: the combined external debt stock rose 15.5 percent from the previous year to $535 billion. Much of this increase was driven by a sharp rise in borrowing by two of the region’s largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, where the external debt stock rose 29 percent and 21 percent respectively.

And now news reports indicate the

And now news reports indicate the