This is from a CGD paper by Scott Morris, Brad Parks, and Alysha Gardner:

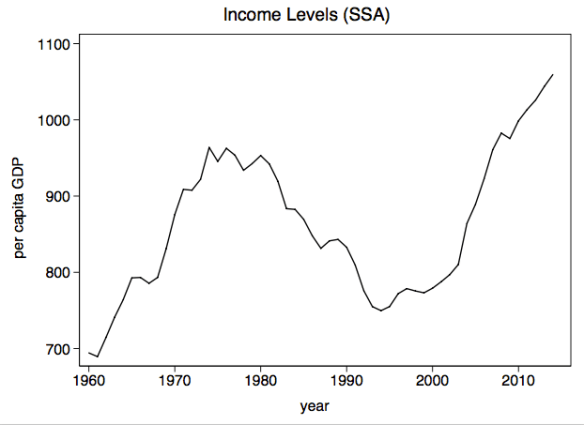

The World Bank’s portfolio is more concessional than China’s portfolio in every region of the world, and sometimes dramatically so. The overall concessionality of China’s portfolio demonstrates less variation from region-to-region, hovering between 15%-22% in all regions except Europe and Latin America. By contrast, the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio varies widely — from a low of 15% in Latin America to a high of 60% in Sub-Saharan Africa (which is also the region where Chinese lending volumes are highest). The differences between China and the World Bank are most stark in Sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio in Sub-Saharan Africa is nearly 60%, China’s portfolio concessionality in the same region is only 22.5% All three measures of lending terms contribute to these differences in portfolio concessionality rates: China consistently has higher interest rates, shorter maturity lengths, and shorter grace periods

Notice that China is neck and neck with the World Bank across Africa, unlike in other regions where Bank lending dominates. What proportion of Chinese lending in Africa are concessional loans?

Whereas the overall concessionality of the World Bank’s portfolio in Sub-Saharan Africa is nearly 60%, China’s portfolio concessionality in the same region is only 22.5% .

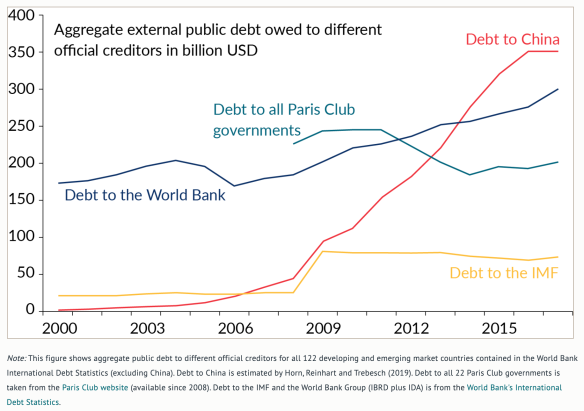

Recall that, overall, China is the single largest creditor to developing countries:

What we should make of African states’ indebtedness to China? A lot of people have opined that China is engaging in debt diplomacy — intentionally trapping African countries with high interest non-concessional loans, after which it will demand all manner of concessions from them (perhaps UN votes, or other forms of assistance in aid of Beijing’s geo-strategic objectives). I have two thoughts on this.

First, the Chinese debt bonanza seen on the Continent over the last two decades was driven, in part, by local demand for infrastructure and other visible and attributable forms of “development.” And yes, intra-elite distributive politics and over-pricing was also involved. And Chinese firms, which often competed against each other, played along, too — perhaps because of the reasons Yuen Yueng Ang describes in her latest book (highly recommended). With this in mind, it is not entirely true to claim that Beijing pushed loans on African states. While it is true that some of the projects were driven more by the quest for kickbacks than for economic reasons, the fact is that individual country dynamics drove the demand for loans and projects. Some of those fit into China’s global geopolitical ambitions (like the Belt and Road Initiative). Others did not.

Second, let’s think through the debt diplomacy game. Is the idea that China would ruin dozens of African states’ fiscal positions so much so that they would turn to Beijing for bailouts? How many Hambantota’s can China run across Africa? Does Beijing have the fiscal, military, or administrative capacity to do so?

The simple fact is that the use of gunboat diplomacy to settle sovereign debts is no longer kosher within the international system. My guess is that while Beijing certainly was out to buy influence with loans and other commercial relations, it also wanted to make money. Chinese officials were not running around peddling cheap concessional loans (see above). They were out looking for business for Chinese firms and banks. And so to the extent that African countries mismanaged their debt or invested in economically unviable infrastructure projects (even if in collusion with Chinese firms), that is on them.

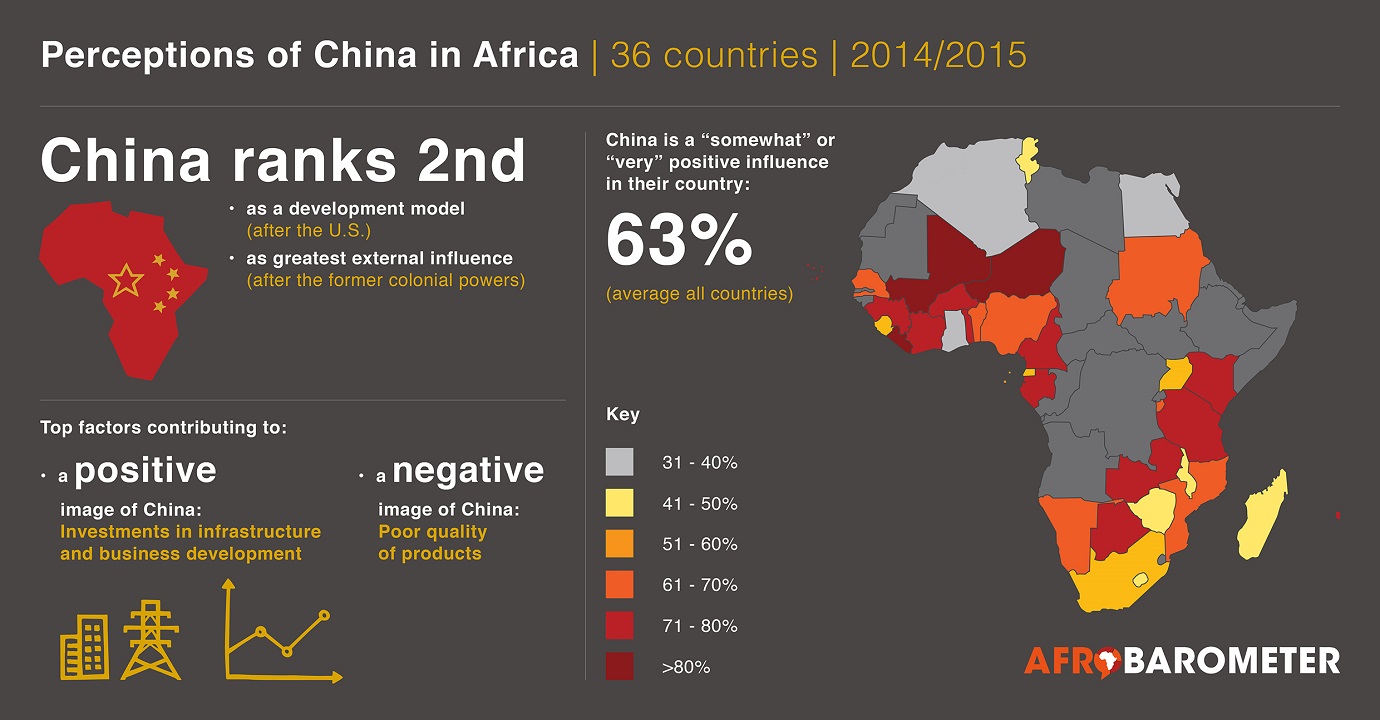

Moving forward, it is clear that it will be in China’s best interest to make sure that its commercial relations in Africa do not stray too far from general economic viability. A strategic coddling of poor and weak allies will be very costly in the long run (see France in the Sahel). It will also likely turn African public opinion against China. For a long time, majorities of African publics have reported net favorable views of China. But this will most likely change if China morphs from a largely likable development partner building roads, power lines, and water works, to little more than a banker of tinpot tyrants in the business of building white elephants and saddling future generations with debt.

… the greening of the planet over the last two decades represents an increase in leaf area on plants and trees equivalent to the area covered by all the Amazon rainforests. There are now more than two million square miles of extra green leaf area per year, compared to the early 2000s – a 5% increase.

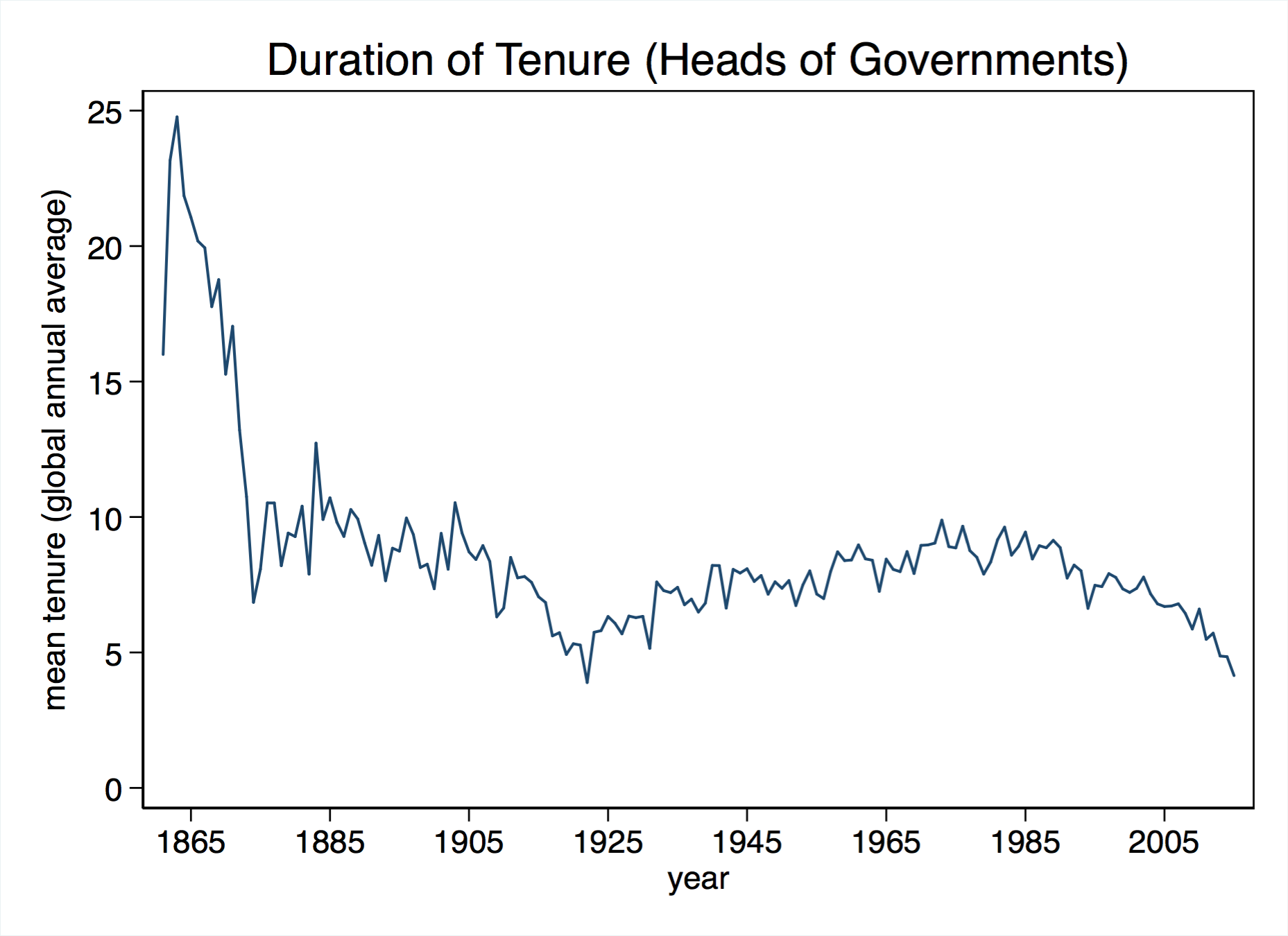

… the greening of the planet over the last two decades represents an increase in leaf area on plants and trees equivalent to the area covered by all the Amazon rainforests. There are now more than two million square miles of extra green leaf area per year, compared to the early 2000s – a 5% increase. …. As the elites’ social networks became localized, they also fragmented; they found it difficult to organize cross regionally. A fragmented elite contributed to a despotic monarchy because it was easier for the ruler to divide and conquer. Historians have noted the shift to imperial despotism during the Song era, as the emperor’s position vis-à-vis his chief advisors was strengthened (Hartwell 1982, 404–405). The trend further deepened when in the late fourteenth century the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty abolished the entire upper echelon of his central government and concentrated power securely in his own hands (Hucker 1998, 74–75). This explains the increasing security of Chinese rulers [see image].

…. As the elites’ social networks became localized, they also fragmented; they found it difficult to organize cross regionally. A fragmented elite contributed to a despotic monarchy because it was easier for the ruler to divide and conquer. Historians have noted the shift to imperial despotism during the Song era, as the emperor’s position vis-à-vis his chief advisors was strengthened (Hartwell 1982, 404–405). The trend further deepened when in the late fourteenth century the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty abolished the entire upper echelon of his central government and concentrated power securely in his own hands (Hucker 1998, 74–75). This explains the increasing security of Chinese rulers [see image]. Germany is the only major Western country that saw its trade volume with African states increase over the same period.

Germany is the only major Western country that saw its trade volume with African states increase over the same period.

A key weakness that I see in the “Let China Fail in Africa” strategy is that it vastly underestimates the extent to which Africans will be willing to work hand in hand with China to make the Sino-African relationship work.

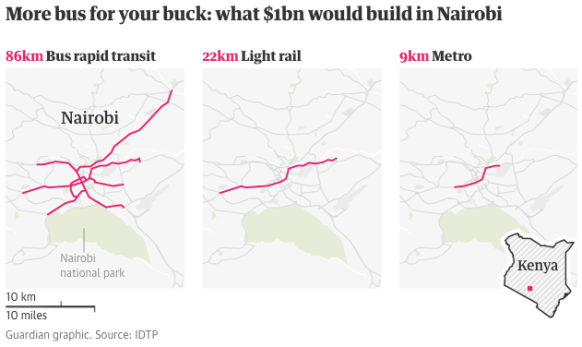

A key weakness that I see in the “Let China Fail in Africa” strategy is that it vastly underestimates the extent to which Africans will be willing to work hand in hand with China to make the Sino-African relationship work. “With a metro, an international firm will often just parachute in its own system,” says Kost. “Bus rapid transit allows existing stakeholders to get involved. That’s what we did in Dar es Salaam and what we’re planning in Nairobi, where the bus bodies will be built in the city and local operators will look after tickets, fare collection and IT. It’s good for the development of the local economy.”

“With a metro, an international firm will often just parachute in its own system,” says Kost. “Bus rapid transit allows existing stakeholders to get involved. That’s what we did in Dar es Salaam and what we’re planning in Nairobi, where the bus bodies will be built in the city and local operators will look after tickets, fare collection and IT. It’s good for the development of the local economy.” Enter the Chinese. Their model is to pay for resources both in cash and in kind. African leaders still get cash that they can stash abroad. But they also get roads, railways, stadia, hospitals, water works, among other infrastructure investments. And more recently Chinese firms have begun to invest in actual factories — most notably in Ethiopia.

Enter the Chinese. Their model is to pay for resources both in cash and in kind. African leaders still get cash that they can stash abroad. But they also get roads, railways, stadia, hospitals, water works, among other infrastructure investments. And more recently Chinese firms have begun to invest in actual factories — most notably in Ethiopia.  This is precisely why life presidencies are sub-optimal. Long tenures eventually convince even the most democratic of leaders that they are above the law. They freeze specific groups of elites out of power. And remove incentives for those in power to be accountable and to innovate.

This is precisely why life presidencies are sub-optimal. Long tenures eventually convince even the most democratic of leaders that they are above the law. They freeze specific groups of elites out of power. And remove incentives for those in power to be accountable and to innovate. Xi’s China is a reminder of that political development is not uni-directional. It is also a caution against trust that elites’ material interests are a bulwark against would-be personalist dictators. China’s economy is booming (albeit at a slower rate of growth), and continues to mint dollar billionaires. Yet the country’s political and economic elites appear helpless in the face of a single man who is bent on amassing unchecked power (the same happens in democracies with “strong western institutions”, too).

Xi’s China is a reminder of that political development is not uni-directional. It is also a caution against trust that elites’ material interests are a bulwark against would-be personalist dictators. China’s economy is booming (albeit at a slower rate of growth), and continues to mint dollar billionaires. Yet the country’s political and economic elites appear helpless in the face of a single man who is bent on amassing unchecked power (the same happens in democracies with “strong western institutions”, too).