For two years it almost seemed too good to be true. Kenya had invaded Somalia and occupied Kismayo, a key Al-Shaabab-held city in southern Somalia without carnage visiting the capital Nairobi. The group instead opted for sporadic attacks against churches and police installations in the border regions of North Eastern and Coast. A few explosions rocked the capital, but these were never spectacular. Indeed, some of them appeared to have been motivated by local business rivalries and not some revenge mission by the Somali Islamist group Al-Shaabab. Within Somalia, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) mission made quick gains that left Al-Shaabab backpedaling. With a few exceptions, the Al-Shaabab was reported to have been severely weakened and on the run. Before the recent uptick in bombings, Mogadishu was slowly becoming a reasonably peaceful boomtown.

A scene from the Westgate Mall siege

And then Westgate happened. At around noon on September 21st three groups of armed men (and allegedly at least one woman) stormed the upscale mall in Nairobi and started shooting indiscriminately. Several hours after the attack started Al-Shaabab claimed responsibility via twitter. A day later, the Islamist group gave an alleged list of the gunmen, all men between the ages of 20-27. Six were from the US, two from Somalia, and one each from Kenya, the UK, Finland and Syria. More than 36 hours after the attack began at least 69 people had been confirmed dead, including one gunman and two Kenyan officers. A visibly incensed President Uhuru Kenyatta condemned the attacks, and reassured Kenyans of a swift response to punish the perpetrators. Just a few minutes earlier Al-Shaabab had claimed responsibility for the attacks, terming them a retribution for Kenya’s invasion of Somalia in 2011. The Kenyan Defence Forces, under Operation Linda Nchi, invaded Somalia following sporadic kidnappings and attacks along the Kenya Somalia border. The forces still remain in Somalia under the command of AMISOM.

So how will Kenya respond? There will be both short-term and long-term responses to the daring terrorist attack. The likely short-term response holds more risk, and may even jeopardize the strategic objectives of the long-term response.

Understandably, in the short-term there is going to be considerable public pressure for a swift military response from the government. In the coming weeks the government’s response will likely involve both domestic crackdowns in suspected Al-Shaabab havens in Kenya (most likely in Nairobi, the Coast and North Eastern regions) and military operations against Al-Shabab targets within Somalia.

police recover suicide bombs in a past operation in Eastleigh (Courtesy of the Star Newspaper)

Crackdowns within Kenya will come with a lot of risk. Depending on how they are carried out, the government could end up walking right into Al-Shaabab’s trap by alienating Kenyan Muslims and ethnic Somalis who make up the majority of residents in Coast and North Eastern regions of the country that border Somalia.

Ethnic Somalis (both Kenyan and Somali nationals) also make up the majority of residents in Eastleigh, a district of Nairobi that has in the past witnessed government crackdowns targeting cells linked to the Al-Shaabab militant group.

Kenyan security forces must therefore proceed with extreme caution to ensure that as few innocent civilians as possible are arrested or roughed up by security forces in any operations within the country. A repeat of reported cases of police brutality in North Eastern following the murder of army officers by gunmen would be a terrible mistake. It is also vital that the government stresses the unity of all Kenyans of all ethnic extractions against terror attacks. Any victimization of ethnic Somalis must be met with swift punishment.

Military operations within Somalia will likely involve significant cooperation with Mogadishu, pro-AMISOM militia in Jubaland, AMISOM and the US and may not be completely under the control of Nairobi. I suspect that Nairobi might push for a more aggressive hunt for the leaders of Al-Shaabab, including Samantha Lewthwaite a.k.a. the “white widow,” a British national that is rumored to have been the mastermind of the Westgate Mall attack. Lewthwaite, the widow of London 7/7/2005 suicide bomber Jermaine Lindsay, is suspected to be on the run in Mombasa, Kenya with her four children. Crucially, any military operations in Somalia must be informed by analysts’ observation that it might be the case that Al-Shabaab is a group on the decline that is just lashing out to maintain relevance.

An outline of the Jubaland region of Somalia

In the long-run, Nairobi will most likely push for a more robust Somali solution to the security crisis posed by the lack of a functional state in its backyard. Top on the agenda will be the strengthening of the security apparatus in the administration of Jubaland, the Somali state that is on the border with Kenya (For a detailed analysis of the situation in Jubaland see here). The creation of Jubaland has long been a goal of the Kenyan government as a buffer against the chaos that has been Somalia for the last two decades. Despite obvious objections from Mogadishu, Nairobi has never publicly denounced this policy goal. The brazen attack in the capital creates even more need for a strong buffer region that can help the Kenyan security forces to deal effectively with a terrorist group that appears desperate and willing to do just about anything to remain relevant. The success of this policy will depend on Mogadishu’s ability to veto it, and support from Ethiopia and AMISOM.

Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somaliland, Puntland and Kenya all have reasons to support the creation of Jubaland, or in general, a more decentralized state in Somalia. Kenya, Djibouti and Ethiopia remain wary of a potential rise in Somali nationalism and any irredentist attempts that might follow to unite all lands that make up the so called Greater Somalia – which would include the Ogaden in Ethiopia, North Eastern region of Kenya, and Djibouti. This is not a crazy fear. Mogadishu once attempted this in the late 1960s in a botched operation (in the Shifta and Ogaden wars) that ultimately led to a military coup and the rise of Siad Barre to power (See Laitin, 1976 [gated]). Ethiopia has the most to worry about regarding this potential risk. The Ogaden remains at the periphery of the Ethiopian state, giving the Somali population lots of reasons to rebel against Addis Ababa.

In the recent past Kenya has experienced an increasing level of integration of the Somali elite into the Kenyan state. Prominent Kenyans of Somali extraction include the leader of Majority in the National Assembly, the Foreign Minister, the Industrialization Minister, the head of the electoral management body (IEBC), among others.

Furthermore, many Somalis both Kenyan and from Somalia have in the recent past made significant investments in Kenya, most notably in the real estate sector. A lot of the investments have been means of laundering money got from illicit activities (some say including piracy). Indeed the governor of the Central Bank of Kenya is on record to have said that he could not account for billions of shillings in the economy. With an estimated total of only 20,000 mortgage accounts, most of the Kenya’s real estate boom has so far been financed by cash.

Yes, a lot more needs to be done for the average Kenyan of Somali extraction in North Eastern region, but the Somali elite in Kenya have every reason to not rock the boat and remain wedded to Nairobi. This same elite has so far tacitly supported Nairobi’s policy regarding the creation of an autonomous region in Jubaland.

The powerful imagery of a picture that went viral showing a Kenyan police officer, who also happens to be an ethnic Somali, carrying a baby while shielding three adults as they ran for safety at Westgate is hard to miss.

A domestic outcome of the Westgate attack will likely be greater scrutiny of the police and intelligence forces. The Kenyan police have been exposed in the past for having looked the other way in exchange for bribes to allow gun-runners to do their thing along the country’s highways. President Kenyatta will likely call for a cleaning of house both at Vigilance House and at the NSIS headquarters. All security agencies will likely see closer scrutiny from the political class and calls to pull up their socks. The minister in charge of internal security, Joseph Ole Lenku, probably has his days numbered on the job.

The quest for greater security will be completed by the proliferation of small arms and light weapons in the country on account of civil wars and general insecurity in the border regions with Uganda, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia. According to a 2012 a study by the Small Arms Survey and the Kenya National Focus Point on Small Arms and Light Weapons, there are between 530,000 and 680,000 firearms in civilian arms across the country. The government must tighten its disarmament operations. Westgate has shown that AK-47s are not just the weapons of cattle rustlers, bank robbers and carjackers.

Will the reforms succeed? Very likely. The Kenya Revenue Authority is a testament to the fact that when it matters, the Kenyan government can reform key state institutions. The security sector is need of just such a reform drive. Insecurity is on the rise across the country, both from common criminals and organized gangs and terrorists. The Kenyan leadership appreciates that insecurity is not just bad in terms of risk to human lives. It is also bad for business.

If Mr. Kenyatta’s first term is to achieve even a modicum of success, the security sector must be reformed.

In all likelihood the president’s quest for a successful first term will outrank a few officers’ venal machinations within the administration. Police ineptitude in dealing with common petty and not-so petty crime creates loopholes for spectacular attacks like Westgate. Reform will therefore need to go beyond capacity building within the Special Forces and dedicated anti-terror units.

For regular Kenyans, life in Nairobi will never be the same again. It is almost impossible to imagine that things that most only read in the news could happen right at home; that a Saturday afternoon at the mall could turn into a ghastly massacre. It will take time before the capital, and the nation, finds its new normal, if at all it does.

Kenyans queue to donate blood at Uhuru Park on Monday Sept. 23rd (Source: The Standard)

So far Kenyans’ resiliency has been outstanding. People showed up in their thousands to donate blood. Buses in Nairobi lowered their fares to take people to blood donation points. More than 40 million Shillings has so far been raised through MPesa for affected victims. Never before in my life have I felt or seen this level of patriotism from fellow Kenyans.

I hope it sticks. Especially because the country will need it in the next few weeks and months as the government formulates and effects a response to the Westgate Mall attack.

According to Sean Avery

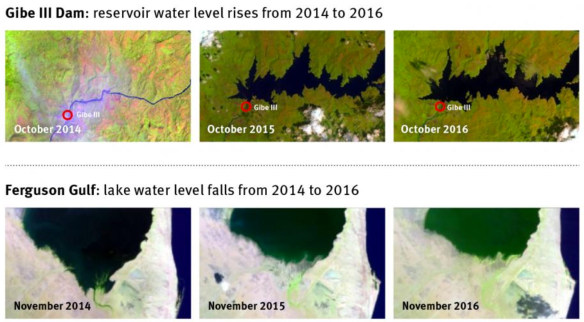

According to Sean Avery At this juncture you may ask, why isn’t the Kenyan government up in arms over the Gibe projects?

At this juncture you may ask, why isn’t the Kenyan government up in arms over the Gibe projects?