The UN Security Council has rejected Kenya’s (and the African Union’s) request for a one year deferral of the case against President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy at the Hague. The two stand accused of crimes against humanity committed following the disputed elections in 2007. More than 1300 people died, and hundreds of thousands were displaced.

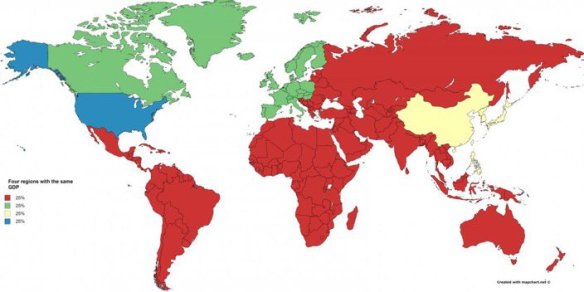

The US, UK, France, Australia, Guatemala, Luxembourg, South Korea and Argentina abstained to stop the deferral request. China, Russia, Togo, Morocco, Pakistan, Azerbaijan and Rwanda voted for a deferral. African leaders have in the last two years been on an ill-advised crusade against the ICC, terming it as a “race hunting” tool of “declining” Western powers.

Kenyatta and Ruto are innocent until proven otherwise, but their attempts to make their personal cases at the ICC a regional struggle of Africans against imagined neo-colonialists bent on usurping African sovereignty is a little misguided. The Kenyan case is different (Kenya is not Sudan or the DRC) and ought to have attracted special consideration from the court (see closing remarks below). However, despite its faults the ICC is all the continent has in the quest to hold its leaders accountable. I reiterate, murderous dictators in Africa and elsewhere should never be allowed to have internal affairs.

Here is the government’s total freak out response following the UNSC vote, with some comments from yours truly.

STATEMENT FROM THE FOREIGN AFFAIRS MINISTRY IN KENYA

Kenya takes note of the outcome of the United Nations Security Council meeting on peace and security in Africa, and specifically on the subject of the request for deferral of the Kenya ICC cases. Kenya wishes to thank China and Azerbaijan who, during their stewardship of the Security Council, have been professional and sensitive to the African Union agenda.

Wow, this is how bad things have become. That Kenya finds friends in states like Azerbaijan. Yes, this is the place in which the president recently announced the election results even before the polls opened. These are our new committed friends. We are going places.

Kenya wishes to thank the seven members of the Security Council who voted for a deferral and is particularly grateful to Rwanda, Togo and Morocco – the three African members on the Security Council – for their exemplary leadership.

Again, the only country we should be associated with on this list is perhaps Rwanda. I wish we could do what they have done with their streets, and corruption, and ease of doing business. But by all means we should not borrow their human rights record. Oh, and please let’s stay away from their variety of democracy.

This result was not unexpected considering that consistently some of the members of the Security Council, who hold veto powers, had shown contempt for the African position. The same members and five others chose to abstain, showing clear cowardice in the face of a critical African matter, and a lack of appreciation of peace and security issues they purport to advocate.

Letting the trial go on does not threaten peace and stability in Kenya. This is an empty argument. There will not be any spontaneous violence. Furthermore, the president is not the operational commander of the KDF. He is the Commander in Chief. He gets to issue orders from some room somewhere. Orders can be issued from anywhere. And remind me again how this trial impacts security ALL OVER AFRICA, other than by raising the cost of genocidal activities by African presidents?

Oh, and did I mention that the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is almost entirely paid for by the European Union?

Inevitably, it must be appreciated that the outcome of this vote demonstrates that the Security Council does not serve the interests of a majority of its members and is clearly in need of urgent reform. It cannot be that a few countries take decisions that go against reason and wisdom in a matter so important to nearly one billion Africans.

One billion Africans. Really? I had no idea our president was this important of a man. One billion Africans. Many of whom starve to death; or die of treatable illnesses; or never make it to their first or fifth birthday because their leaders steal all the money meant for medicine. These Africans? Why should their names be invoked to protect the same leaders that have confined them to degrading penury for the last half century? Why, I ask?

Also, the claim that Africa is united against the ICC is false. We all know about the divisions that stalled the silly idea of a mass walkout from the ICC by African states.

The African Union, in one voice, took the unprecedented step of making a simple request to the Security Council, bearing in mind the security and stability it seeks to achieve on the continent. But the Security Council has failed to do this and humiliated the continent and its leadership.

Ahh. Now the truth comes out. It is not about the one billion Africans after all. This is about the humiliation of the African leadership. It is about protecting the sovereignty of a few inept rulers. Forget the one billion Africans. It is about their big men rulers who steal tax money and stash it away in bank accounts in the same Western countries they like to call names.

The Security Council has failed the African continent, which will have to make its own judgment in the coming days and weeks about how it wishes to engage with the Security Council, which obviously does not believe the voices of more than one quarter of its members is significant enough to warrant its serious and purposive attention.

The security council has failed African leaders. Not the African people en masse. Africans want to have elections without having to worry that voting one way or the other will result in their houses being torched or their mothers, sisters and brothers murdered or raped. They also want freedom from ignorance, disease and material want. Is that too much to ask?

The African Union’s request to the Security Council included its key resolutions at the Special Summit on the ICC. The important one for the Security Council to note was the one that categorically says that no sitting Heads of State or Government may appear before the ICC. Kenya regrets failure of important members of the UN Security Council to have due consideration of Kenya’s critical role in stabilizing the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes regions, and their reckless abdication of global leadership.

Wait, are these important global leaders in the UNSC the same ones President Kenyatta termed as “declining powers”? What makes them important now?

Just for the record, I am part of the 67% of Kenyans who in a recent poll were in favor of the president attending court at the Hague. Having both the president and his deputy on trial will serve a great symbolic task of demystifying the Kenyan political leadership. The demonstration effect to all politicians, voters and criminal gangs alike will be clear: You cannot kill innocent civilians and get away with it.

In my view, the best case scenario is having both men attend trial and then get a not guilty verdict.

Kenyans are nowhere near ready to discuss frankly what happened in 2007-08 or the deeper issues of ethnicity and economic disparities that often mirror ethnic lines and how to deal with these issues at the national level. A forced conversation, especially one that has a foreign touch in the form of a court verdict, may result in unpleasant consequences. This would be a less than ideal outcome, but one that would not necessarily be catastrophic for the country. The constitution is clear on succession should either one or both leaders be found guilty and jailed.