A piece in the New York Times highlights some of the Africa-related queries posed by Team Trump to the State Department. Sub-Saharan Africa’s 48 countries get $8b in U.S. aid each year. The average country receives far less than critical U.S. allies like Afghanistan ($5.5 billion), Israel ($3.1 billion), Iraq ($1.8 billion) and Egypt ($1.4 billion).

Here are some answers to Team Trump’s questions.

With so much corruption in Africa, how much of our funding is stolen? Why should we spend these funds on Africa when we are suffering here in the U.S.?

First of all, corruption is not the biggest impediment to success in the aid business. Often, it is poor planning and execution. And most of the time this tends to be the fault of the donors themselves. Research shows that aid works best when complemented with strong local capacities. This requires knowing what those capacities are, or investing in their long term development.

I would suggest that the administration worries more about planning and execution. How can you make your aid agencies better at identifying and executing on projects? How can you help African countries improve their absorption capacity of aid dollars without too much distortion of their local political economies? How can you move away from projects predicated on good will, and into ones that are anchored on self-interest and value creation?

Africans want jobs. Not handouts. And the 0.2% of the U.S. budget that goes to this region each year can be a powerful tool for shifting incentives in the right direction as a far as job creation is concerned. Want to export more GM cars or carrier air conditioning units to Lagos? Then help create the demand by creating jobs in Lagos.

The new administration should also end the double talk of financing corruption and condemning it at the same time.

Take the example of security assistance. If you want to reduce corruption in military procurement, I would suggest that you channel all assistance through the normal appropriation processes in African legislatures. More people will know how much money is going where, thereby increasing the likelihood of greater accountability. The same applies for budget support. Strengthen existing constitutional appropriation processes so that bigger constituencies get to own the aid dollars.

Take the example of security assistance. If you want to reduce corruption in military procurement, I would suggest that you channel all assistance through the normal appropriation processes in African legislatures. More people will know how much money is going where, thereby increasing the likelihood of greater accountability. The same applies for budget support. Strengthen existing constitutional appropriation processes so that bigger constituencies get to own the aid dollars.

Leaders do terrible things all the time for political reasons, and not because of an inherent failure in moral judgment. Learn to respect and trust your African counterparts. Know their interests. Don’t think and act like it is 1601.

We’ve been fighting al-Shabaab for a decade, why haven’t we won?

Well, for a number of reasons. Kenya, Ethiopia, the U.S., and the other TTCs are working at cross-purposes. The first best option would be to strengthen Mogadishu as the center of a strong unitary state. But no one wants that. Not the Somalian elites running the state-lets that make up the federal state. Not Kenya — whose goal seems to be no more than creating a buffer stable region in Jubaland. Not Ethiopia — whose elites are more concerned about Pan-Somalia irredentism and their own domestic politics. And certainly not the TTCs — who are largely in it for the money and other favors from Washington and Brussels. The second best option would probably be to localize the Al-Shabaab problem and then strengthen the Somali state-lets so that they can be able to fight the group. However, by globalizing the “war on terror” the U.S. has largely foreclosed this option. Also, Mogadishu would not want to cede too much military power to the states.

All to say that the U.S. cannot win the fight against al-Shabaab, certainly not by raining fire from the air.

Somalians, with some help from their neighbors, are the best-placed entity to win the war. But for this to happen, all actors involved — and especially Ethiopia and Kenya — must have an honest discussion about both short-term and long-term objectives of their involvement, and the real end game.

Most of AGOA imports are petroleum products, with the benefits going to national oil companies, why do we support that massive benefit to corrupt regimes?

Again, you should not approach this problem from the perspective of a saintly anti-corruption crusader. Moralizing from the high mountains is boring, and does not solve anything. I thought the Trump Team would be into dealing with the world as it is. Appeal to the specific interests involved. Think creatively.

It turns out that public finance management is a lot harder than most people think. Don’t expect people to be honest and patriotic. Help design PFM systems that are robust to the worst of thieves.

Here, too, I would suggest a move towards mainstreaming resource sector transactions into the normal appropriation processes. For instance, the administration can introduce greater transparency in the oil business, and create stronger links between oversight authorities in the host countries and the American firms involved. This will not end corruption, but it will serve to disperse power within the oil producing countries. And that would be a good thing.

Also, a quick reminder that AGOA involves more than just oil. Africa’s tiny textiles sector benefits too. Doing more to develop this sector would create tens of thousands of jobs, thereby reducing aid dependence.

We’ve been hunting Kony for years, is it worth the effort?

Nope.

The LRA has never attacked U.S. interests, why do we care? Is it worth the huge cash outlays? I hear that even the Ugandans are looking to stop searching for him, since they no longer view him as a threat, so why do we?

I have no idea.

May be this has been used as a way of maintaining ties with the Ugandan military in exchange for continued cooperation in central Africa and in Somalia? May be it is a secret training mission for the U.S. military in central Africa?

I honestly have no idea.

Is PEPFAR worth the massive investment when there are so many security concerns in Africa? Is PEPFAR becoming a massive, international entitlement program?

PEPFAR has saved millions of lives. And I would argue that it is probably America’s most important investment in soft power across Africa.

I would suggest a few modifications, though. The new administration should think creatively about how to use PEPFAR dollars to strengthen African public health *systems* in a manner that will allow them to provide effective care beyond HIV/AIDS. Malaria and GI diseases kill way more people. These need attention, too.

How do we prevent the next Ebola outbreak from hitting the U.S.?

By strengthening public health systems in countries that are likely to experience Ebola outbreaks.

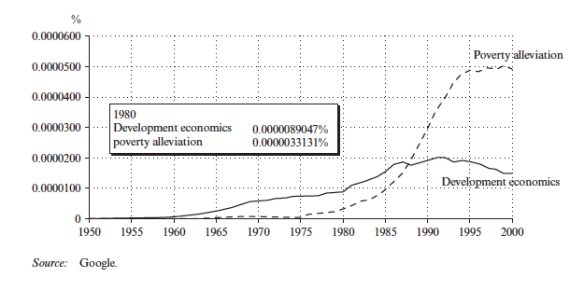

The editors also find that the basic fact of uneven development tends to be reduced to models of “dualism,” which implies less attention to the differentiation internal to sectors, and patterns of interaction of different groups of classes within and across sectors. Furthermore, when it is discovered that certain institutions are different from “the norm” in developing countries, they are highlighted and explained using the same basic analytical tools developed for the norm. This type of Economics is what the editors call a National Geographic view of the broader process of development, as only snapshots of particular institutions or economic activities are separated for the analysis.

The editors also find that the basic fact of uneven development tends to be reduced to models of “dualism,” which implies less attention to the differentiation internal to sectors, and patterns of interaction of different groups of classes within and across sectors. Furthermore, when it is discovered that certain institutions are different from “the norm” in developing countries, they are highlighted and explained using the same basic analytical tools developed for the norm. This type of Economics is what the editors call a National Geographic view of the broader process of development, as only snapshots of particular institutions or economic activities are separated for the analysis. The answer has to do with the the relative political power of the European settler community, especially after UDI. Since 1923 the group had enjoyed effective self-government with significant autonomy from London. And it is precisely because of their political power that

The answer has to do with the the relative political power of the European settler community, especially after UDI. Since 1923 the group had enjoyed effective self-government with significant autonomy from London. And it is precisely because of their political power that

Take the example of security assistance. If you want to reduce corruption in military procurement, I would suggest that you channel all assistance through the normal appropriation processes in African legislatures. More people will know how much money is going where, thereby increasing the likelihood of greater accountability. The same applies for budget support. Strengthen existing constitutional appropriation processes so that bigger constituencies get to own the aid dollars.

Take the example of security assistance. If you want to reduce corruption in military procurement, I would suggest that you channel all assistance through the normal appropriation processes in African legislatures. More people will know how much money is going where, thereby increasing the likelihood of greater accountability. The same applies for budget support. Strengthen existing constitutional appropriation processes so that bigger constituencies get to own the aid dollars.