Bloomberg reports:

Kenya is competing with Tanzania to build the pipeline from oilfields in Hoima, western Uganda. It would either traverse northern Kenya’s desert to a proposed port at Lamu, near the border with Somalia, or south past Lake Victoria to Tanga on Tanzania’s coast. A third option would be through the southern Kenyan town of Nakuru.

Kenya is competing with Tanzania to build the pipeline from oilfields in Hoima, western Uganda. It would either traverse northern Kenya’s desert to a proposed port at Lamu, near the border with Somalia, or south past Lake Victoria to Tanga on Tanzania’s coast. A third option would be through the southern Kenyan town of Nakuru.

Tanzanian President John Magufuli said earlier this month he’d agreed with Museveni to route the conduit via his country at a cost of about $4 billion, with funding from Total SA. The Kenyan option favored by Tullow, which has oil discoveries in Uganda and Kenya, may cost $5 billion, according to an estimate by Nagoya, Japan-based Toyota Tsusho Corp.

Uganda is in a rush to get its oil to market. It also wants to make sure that it does not tie its hands in an obsolescing bargain with Kenya. Being landlocked, the country already depends a great deal on Kenya as an overland route for its imports and exports. The pipeline would add to Nairobi’s bargaining power vis-a-vis Kampala.

In an open letter to President Yoweri Museveni, Angelo Izama, a Ugandan journalist (and a friend of yours truly) articulates these concerns and concludes that it is better for Uganda to build the pipeline through Tanzania in order to minimize its political risk exposure:

It is not rocket science that routing both commercial traffic and oil through Kenya would give Nairobi near total influence on economic matters and would, added to Kenya’s already considerable market penetration in Uganda, leave little wiggle-room for unforeseen and some predictable hazards. The Ugandan domestic commercial and industrial community as well as consumers remember well how helpless they were when disruptions followed the Kenyan election of 2007 (even when some of us had urged the government earlier to restock fuel in anticipation of political violence). Many also live with the challenges of a single port to our import-addicted economy and the cost to family fortunes whenever Nairobi pulls bureaucratic red tape. Obviously being landlocked is not a “non-issue” as you framed it in Kyankwanzi. It needs to be placed in a detailed context. I have some reservations over your optimistic take on political and market integration, and that said, clearly having one member, in this case Kenya, within this greater EAC community with more power and influence than the rest is not an advantage to the growth of the community and may in fact prove rather dangerous. This as I recall has been the common fear cited in our neighbourhood about Uganda’s aggressive military spending (to which the Kenyan government responded with its own expenditure in the decade ending 2018).

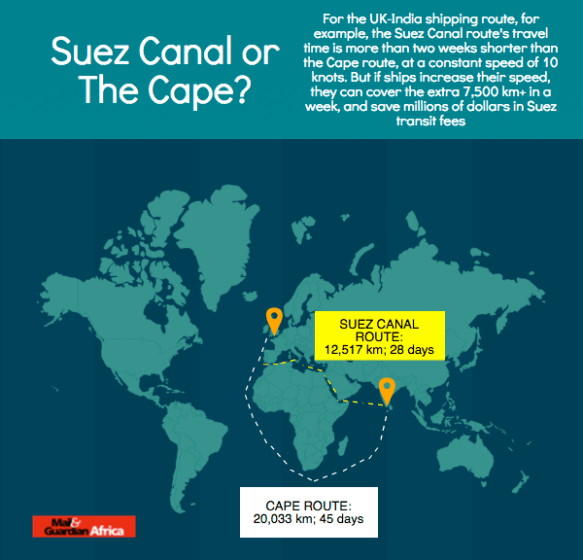

The official reason given by Uganda for considering the Tanzania option (see map) is that construction of the Kenyan pipeline would be delayed (due to corruption, expensive land [Kenyans and land!], security threats from al-Shabaab, and the fact that the Lamu Port is yet to be completed).

All these are reasonable concerns.

Plus, it would have been foolish for Uganda not to strengthen its bargaining position by CREDIBLY demonstrating that it is considering BOTH options.

But Uganda must also know that whatever the outcome, this is an obsolescing bargain. Once the pipeline is constructed, it will be at the mercy of the host country government.

It is for this reason that it should seriously consider the kinds of future governments that might be in office in Nairobi and Dodoma/Dar es Salaam.

To this end Ugandan policymakers need to ask themselves the question: Would you rather deal with a government that partially answers to private sector interests and operates in a context of weak parties; or do you want to be at the mercy of a party-state in which some politically-motivated party stalwarts can actually influence official policy?

Understood this way, Uganda’s concern should be about what happens after the deal has been sealed; rather than the operational concerns that have thus far been raised by Kampala.

Notice that Kenya has been able to protect its existing oil pipeline well enough. Rioters may have uprooted the railway in 2007, but that was because they felt that Museveni was supporting their political opponent (Museveni could be more discreet in the future). Also, it is a lot harder to uproot a pipeline buried in the ground. The construction delays due to land issues can also be solved (and in Kenyan fashion, at whatever cost) — notice how fast Kenya is building the new standard gauge (SGR) railway line from Mombasa to Nairobi despite the well documented shenanigans around land compensation (More on this in a World Bank report I co-authored in my grad school days here).

Perhaps more importantly, the Kenyan option is attractive because Kenya also has oil, and will have to protect the pipeline anyway. This scenario also guarantees a private sector overlap between the two countries — in the form of Tullow or whoever buys its stake — that will be in a position to iron out any future misunderstandings.

Tanzania is also an attractive option. The pipeline will be $1 billion cheaper. Because it passes through largely uninhabited land, construction will be speedy. And the port at Tanga is a lot further from the Somalia border than Lamu, and should be easier to protect.

All this to say that the operational concerns raised by Kampala are a mere bargaining tool. These issues can be ironed out regardless of the host country. The big question is what happens AFTER the pipeline is constructed.

And here, I don’t see why Tanzania is necessarily a slam dunk.

The history of the EAC (see here for example) tells us that Kenya tends to subject its foreign policy to concentrated private interests. Tanzania on the other hand has a record of having a principled an ideologically driven (and sometimes nationalist) foreign policy with significant input from well-placed party officials. Put differently, the calculation of political risk in Kenya involves fewer structural veto players than in Tanzania. Ceteris paribus, it seems that it would be cheaper to manage the long-run political risk in Kenya than in Tanzania.

That said, the Tanzania option makes a lot of sense in a zero sum game. As Angelo puts it:

I have some reservations over your [Museveni’s] optimistic take on political and market integration, and that said, clearly having one member, in this case Kenya, within this greater EAC community with more power and influence than the rest is not an advantage to the growth of the community and may in fact prove rather dangerous.

But even this consideration only makes sense in the short run. Assuming all goes well for Tanzania, in the long run the country’s economy is on course to catch up to Kenya’s. Dodoma will then have sufficient political and economic muscle to push around land-locked Uganda if it ever so wishes.

To reiterate, the simple question Museveni should ask himself is: who would you rather negotiate with once the pipeline is built?

I don’t envy the Ugandan negotiators. And they have not helped themselves by publicly stating their eagerness to get their oil to market ASAP.

A federal structure, whose prime objective was to maintain security by curbing regional and ethnic influence, does not foster development. Despite receiving about half the national revenue – a sum of N2.7 trillion in 2014 (US$13.5 billion at current official exchange rate) – state governments fail to provide the services that could materially improve the lives of tens of millions of Nigerians. The 2015 United Nations Human Development Index ranked Nigeria 152nd out of 187 countries. State authorities are not accountable to citizens, state institutions are weak and corruption is endemic. The 774 LGAs – the most proximate form of government for most Nigerians – have all but ceased to function. Furthermore, groups armed by or linked to state governors have been responsible for the most deadly outbreaks of violence of the past decade: ethnic clashes in Plateau state, conflict in the Niger Delta and the Boko Haram insurgency.

Kenya is competing with Tanzania to build the pipeline from oilfields in Hoima, western Uganda. It would either traverse northern Kenya’s desert to a proposed port at Lamu, near the border with Somalia, or south past Lake Victoria to Tanga on Tanzania’s coast. A third option would be through the southern Kenyan town of Nakuru.

Kenya is competing with Tanzania to build the pipeline from oilfields in Hoima, western Uganda. It would either traverse northern Kenya’s desert to a proposed port at Lamu, near the border with Somalia, or south past Lake Victoria to Tanga on Tanzania’s coast. A third option would be through the southern Kenyan town of Nakuru. Compared with other fast-growing economies, Kenya invests less and the share of investment financed by foreign savings is higher. The economic literature and post-World War II history illustrate that investment determines how fast an economy can grow. Kenya’s investment, at around 20 percent of GDP, is lower than the 25 percent of GDP benchmark identified by the Commission on Growth and Development (2008). Kenya’s investment rate, as a share of GDP, has also been several percentage points lower than the rate in its peer countries. At the same time, the economy has largely relied on foreign savings as a source for new investment since 2007, while national savings have been declining. National savings—measured as a share of gross national disposable income (GNDI)—has not surpassed the 15 percent mark over the past decade. In contrast, Pakistan’s savings is above 20 percent of GNDI, and Vietnam’s is more than 25 percent. Cambodia had a low savings rate in the 1990s, but it more than doubled the rate in the 2000s.

Compared with other fast-growing economies, Kenya invests less and the share of investment financed by foreign savings is higher. The economic literature and post-World War II history illustrate that investment determines how fast an economy can grow. Kenya’s investment, at around 20 percent of GDP, is lower than the 25 percent of GDP benchmark identified by the Commission on Growth and Development (2008). Kenya’s investment rate, as a share of GDP, has also been several percentage points lower than the rate in its peer countries. At the same time, the economy has largely relied on foreign savings as a source for new investment since 2007, while national savings have been declining. National savings—measured as a share of gross national disposable income (GNDI)—has not surpassed the 15 percent mark over the past decade. In contrast, Pakistan’s savings is above 20 percent of GNDI, and Vietnam’s is more than 25 percent. Cambodia had a low savings rate in the 1990s, but it more than doubled the rate in the 2000s.

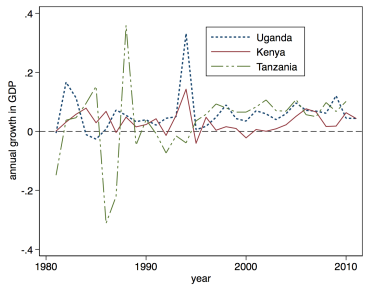

Uganda’s post civil war economic recovery may have been impressive (see graph), but it should no longer be something for Museveni to hang his hat on. It is clear that the longer Museveni stays in office, the more he is going to undo his very own achievements in the earlier years of his three-decade rule.

Uganda’s post civil war economic recovery may have been impressive (see graph), but it should no longer be something for Museveni to hang his hat on. It is clear that the longer Museveni stays in office, the more he is going to undo his very own achievements in the earlier years of his three-decade rule.