Kenya will hold a General Election on August 8th of this year. The national-level elections will include races for president, members of the National Assembly, and the Senate. County-level races will include those for governor (47) and members of County Assemblies (in 1450 wards).

This post kicks off the election season with a look at the presidential election. I also plan to blog about the more exciting gubernatorial races in the coming weeks.

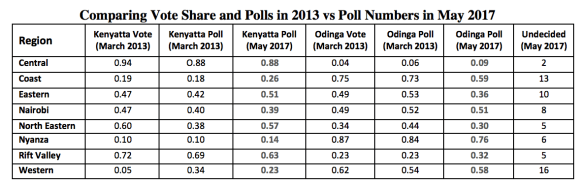

Like in 2013, the contest will be a two-horse race between President Uhuru Kenyatta (with William Ruto as his running mate) and Hon. Raila Odinga (with Kalonzo Musyoka). The convergence on a de facto bipolar political system is a product of Kenya’s electoral law. The Constitution requires the winning presidential candidate to garner more than half of the votes cast and at least 25 percent of the votes in at least 24 counties. In 2013 Kenyatta edged out Odinga in a squeaker that was decided at the Supreme Court. Depending on how you look at it, Kenyatta crossed the constitutional threshold of 50 precent plus one required to avoid a runoff by a mere 8,632 votes (if you include spoilt ballots) or 63, 115 (if you only include valid votes cast). In affirming Kenyatta’s victory, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the latter approach.

But despite the court’s ruling, a significant section of Kenyans still believe that Kenyatta rigged his way into office, and that Odinga should have won.

My own analysis suggests that it was a little bit more complicated. I am fairly confident that Kenyatta beat Odinga in the March 2013 election. But I do not think that he crossed the 50 percent plus one threshold required to avoid a runoff. At the same time, I am also confident that Kenyatta would have won a runoff against Odinga. All to say that I think the results in 2013 reflected the will of the people bothered to vote.

This year will be equally close, if not closer.

This is for the following reasons:

- Odinga has a bigger coalition: The third candidate in 2013, Musalia Mudavadi, is joining forces with Odinga this time round – as part of the National Super Alliance (NASA). Mudavadi managed to get just under 4% last time and will provide a much-needed boost to Odinga’s chances in Western Kenya and parts of the Rift Valley.

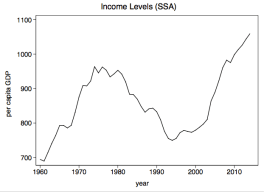

- Kenyatta has had a mixed record in office: The Kenyan economy has grown at more than 5% over the last four years. The same period saw massive investments in infrastructure — including a doubling of the share of the population connected to the grid and a brand new $4b railway line connecting Nairobi to the coast. However, these impressive achievements have been offset by incredible levels of corruption in government – with senior government officials caught literally carrying cash in sacks. Kenyatta is also stumbling towards August 8th plagued with bad headlines of layoffs and the ever-rising cost of living. Barely two months to the election, the country is in the middle of a food crisis occasioned by a failure to plan and a botched response that appears to have been designed to channel funds to cronies of well-connected officials.

- The Rift Valley: In 2013 much of the Rift Valley was a lock for Kenyatta (it is William Ruto’s political back yard). This time will be different. Parts of Ruto’s coalition in the Rift, particularly in Kericho and Bomet counties, may swing towards Odinga this year. All Odinga needs is about a third of the votes in these counties. I expect both campaigns to spend a lot of time trying to sway the small pockets of persuadable voters in these two counties.

- The Kenyatta Succession in 2022: In 2013 Kenyatta was elected as the head of an alliance, not a party. In 2017 he is running atop a party, the Jubilee Party (JP). It is common knowledge that JP is William Ruto’s project. Because he plans to succeed Kenyatta in 2022, he desperately needs credible commitment from Kenyatta and his allies that they will support his bid when the time comes. JP is an installment towards this goal, and is designed to allow Ruto to whip party members in line during Kenyatta’s second term (on a side note, Ruto needs to read up on the history of political parties in Kenya). But by forcing everyone into one boat, JP may actually end up suppressing turnout in key regions of the country, the last thing that Kenyatta needs in a close election.

- The ICC factor (or lack thereof): Because of their respective cases at the ICC, 2013 was a do or die for Kenyatta and Ruto (and their most fervent supporters). This time is different. Both politicians are no longer on trial at the ICC, and so cannot use their cases to rally voters. The lack of such a strong focal rallying point will be a test for Kenyatta’s turnout efforts.

Nearly all of the above factors sound like they favor Odinga. Yet Kenyatta is still the runaway favorite in this year’s election. And the reason for that is turnout.

As I show in the figure below, the turnout rates were uniformly high (above 80%) in nearly all of the 135/290 constituencies that Kenyatta won in 2013. Pro-Odinga constituencies had more spread, with the end result being that the candidate left a lot more votes on the table.

The same dynamics obtained at the county level (see above). In 2013 Odinga beat Kenyatta in 27 of the 47 counties. The counties that Odinga won had a total of 8,373,840 voters, compared to 5,977,056 in the 20 counties won by Kenyatta. The difference was turnout. The counties won by Odinga averaged a turnout rate of 83.3%. The comparable figure for counties won by Kenyatta was 89.7%. At the same time, where Kenyatta won, he won big — averaging 86% of the vote share. Odinga’s average vote share in the 27 counties was a mere 70%.

The same patterns may hold in 2017. The counties won by Odinga currently have 10,547,913 registered voters, compared to 7,556,609 in counties where Kenyatta prevailed. This means that Odinga still has a chance, but in order to win he will have to run up the numbers in his strongholds, while at the same time getting more of his voters to the polls. Given the 2017 registration numbers, and if the turnout and vote share patterns witnessed in 2013 were to hold this year, then Kenyatta would still win with 8,000,936 votes (51.5%) against Odinga’s 7,392,439 votes (47.6%).

The slim hypothetical margin should worry Kenyatta and his campaign team. For instance, with an 89% turnout rate and an average of 85% vote share in the 27 counties Odinga won, and holding Kenyatta’s performance constant, the NASA coalition could best Jubilee this August by garnering 8,921,050 votes (55.4%) vs 7,191,975 (44.6%).

Kenyatta is the favorite to win this August on account of incumbency and Jubilee’s turnout advantage. But it is also the case that the election will be close, and that even a small slip up — such as a 3 point swing away from Jubilee between now and August 8th — could result in an Odinga victory.

2. The number electoral units (wards or constituencies) had no influence on the rate of voter registration in the 47 counties. In other words, it is not the case that counties which had a lot more electoral units (and therefore potential candidates) experienced greater rates of voter mobilization for registration.

2. The number electoral units (wards or constituencies) had no influence on the rate of voter registration in the 47 counties. In other words, it is not the case that counties which had a lot more electoral units (and therefore potential candidates) experienced greater rates of voter mobilization for registration. 3. However, the population per electoral unit (wards and constituencies) was negatively correlated with the registration rate. In other words, more populous wards and constituencies experienced lower registration rates relative to their less populous counterparts. This makes sense, to the extent that the IEBC was targeting a specific number of BVR kits per electoral unit per county.

3. However, the population per electoral unit (wards and constituencies) was negatively correlated with the registration rate. In other words, more populous wards and constituencies experienced lower registration rates relative to their less populous counterparts. This makes sense, to the extent that the IEBC was targeting a specific number of BVR kits per electoral unit per county. 4. Bigger counties with relatively smaller populations benefited from the fact that land area was a consideration in IEBC’s allocation of BVR kits.

4. Bigger counties with relatively smaller populations benefited from the fact that land area was a consideration in IEBC’s allocation of BVR kits.