This is from the organized crime and corruption reporting project (OCCRP):

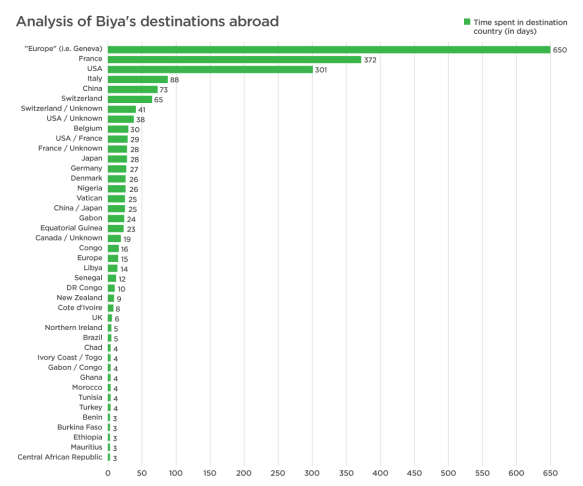

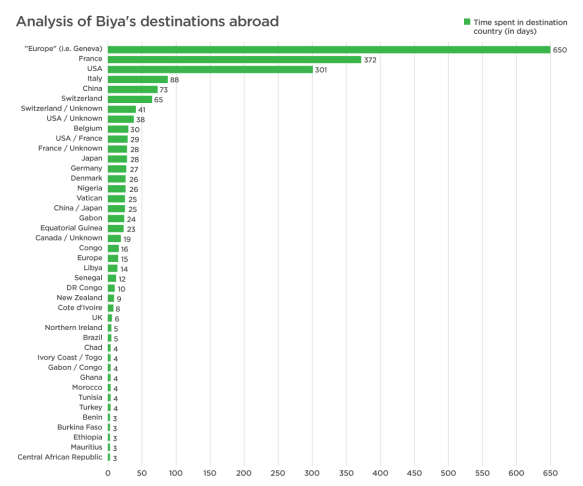

An investigation supported by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) gathered information about the president’s travels from 35 years of editions of the daily government paper, the Cameroon Tribune. They show that, over that time, Biya has spent at least four-and-a-half years [abroad] on his “brief private visits.” This total excludes official trips, which add up to an additional year. In some years, like 2006 and 2009, Biya has spent a third of the year out of the country.

And here is a breakdown of Biya’s destinations over the last three and a half decades. It is almost as if Biya is a colonial governor of Cameroon, a Fanonian caricature.

How does Biya pay for all this travel (estimated to be at least $185m in total)?

….. According to the International Monetary Fund, more than $300 million of the revenue of Cameroon’s national oil company in 2017 was not accounted for. The president has oversight over the company, whose oil sales, according to a leaked US diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks, have historically been used as a slush fund.

Needless to say, the fascination with Geneva leaves little time for Biya to actually govern.

When Biya lands in Yaoundé, he also meets his government — at the airport. Formal ministerial councils are organized infrequently, every year or two at the most. But while Biya has used public funds to sustain a bureaucracy of 65 ministers and state secretaries, he mostly governs by decree or through a handful of laws sped through a rubber-stamp parliament.

Biya signs a flurry of acts between each of his trips. For example, in 2017, he signed a dozen laws — the entire legal output for that year – in a couple of days. It took him just three days to sign the entire year’s decrees.

Strong leadership can make a big difference in states with weak bureaucracies. But unfortunately for Cameroon, for 35 years it has been saddled with both an absentee landlord of a president and a barely coherent public service.

An enduring puzzle is why Cameroonian elites haven’t moved to come up with a more economically efficient means of keeping Biya in power and luxury. For instance, they could make him King, and have him sign decrees whenever he likes, but also have a Prime Minister that is responsible to a parliament and accountable to the people. Not that this would magically improve the quality of governance, but at a minimum, would likely introduce coherence within the public service (unless, of course, all of Cameroon’s elites simply want to appropriate public resources and spend their time in Geneva).

A response to this might be that elites in Cameroon are actually fine, constantly scheming and fighting for favor with Biya and access to governance rents.

But this still leaves open the question of why they wouldn’t want a more predictable means of accessing governance rents — that is not subject to the whims of Biya (who shuffles and jails ministers with wanton abandon). In any case, an elite-level collusion outcome — like the one described above — would create opportunities for the expansion of the pie beyond just oil and other natural resource sectors.

All to say that we should probably be spending more time exploring the seeming lack of elite-level political innovation across Africa (and Political Development more generally).

Despite significant efforts, Africa has struggled to imitate the rapid agricultural growth that took place in Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. As a rare but important exception, Ethiopia’s agriculture sector recorded remarkable rapid growth during 2004–14. This paper explores this rapid change in the agriculture sector of this important country – the second most populous in Africa. We review the evidence on agricultural growth and decompose the contributions of modern inputs to growth using an adjusted Solow decomposition model.

Despite significant efforts, Africa has struggled to imitate the rapid agricultural growth that took place in Asia in the 1960s and 1970s. As a rare but important exception, Ethiopia’s agriculture sector recorded remarkable rapid growth during 2004–14. This paper explores this rapid change in the agriculture sector of this important country – the second most populous in Africa. We review the evidence on agricultural growth and decompose the contributions of modern inputs to growth using an adjusted Solow decomposition model. We also highlight the key pathways Ethiopia followed to achieve its agricultural growth. We find that land and labor use expanded significantly and total factor productivity grew by about 2.3% per year over the study period. Moreover, modern input use more than doubled, explaining some of this growth. The expansion in modern input use appears to have been driven by high government expenditures on the agriculture sector, including agricultural extension, but also by an improved road network, higher rural education levels, and favorable international and local price incentives.

We also highlight the key pathways Ethiopia followed to achieve its agricultural growth. We find that land and labor use expanded significantly and total factor productivity grew by about 2.3% per year over the study period. Moreover, modern input use more than doubled, explaining some of this growth. The expansion in modern input use appears to have been driven by high government expenditures on the agriculture sector, including agricultural extension, but also by an improved road network, higher rural education levels, and favorable international and local price incentives. This is precisely why life presidencies are sub-optimal. Long tenures eventually convince even the most democratic of leaders that they are above the law. They freeze specific groups of elites out of power. And remove incentives for those in power to be accountable and to innovate.

This is precisely why life presidencies are sub-optimal. Long tenures eventually convince even the most democratic of leaders that they are above the law. They freeze specific groups of elites out of power. And remove incentives for those in power to be accountable and to innovate. Xi’s China is a reminder of that political development is not uni-directional. It is also a caution against trust that elites’ material interests are a bulwark against would-be personalist dictators. China’s economy is booming (albeit at a slower rate of growth), and continues to mint dollar billionaires. Yet the country’s political and economic elites appear helpless in the face of a single man who is bent on amassing unchecked power (the same happens in democracies with “strong western institutions”, too).

Xi’s China is a reminder of that political development is not uni-directional. It is also a caution against trust that elites’ material interests are a bulwark against would-be personalist dictators. China’s economy is booming (albeit at a slower rate of growth), and continues to mint dollar billionaires. Yet the country’s political and economic elites appear helpless in the face of a single man who is bent on amassing unchecked power (the same happens in democracies with “strong western institutions”, too).