The situation in Burundi is deteriorating, fast.

There are strong signs of ethnic violence. More than 300 people have been killed since President Pierre Nkurunziza successfully violated term limits to stay in office for a third term early this year. The ensuing violence has forced over 220,000 to flee the country, while scores remain displaced internally. Over the last week alone more than 80 people have been murdered in what is increasingly looking like a civil war rather than mere civil unrest met with heavy-handed repression. The African union has used the word “genocide” in reference to the Burundian situation.

There are strong signs of ethnic violence. More than 300 people have been killed since President Pierre Nkurunziza successfully violated term limits to stay in office for a third term early this year. The ensuing violence has forced over 220,000 to flee the country, while scores remain displaced internally. Over the last week alone more than 80 people have been murdered in what is increasingly looking like a civil war rather than mere civil unrest met with heavy-handed repression. The African union has used the word “genocide” in reference to the Burundian situation.

For a background on the current Burundian crisis see here, here, here and here.

So given the clear evidence that things are falling apart in Burundi, why isn’t the East African Community (EAC) doing more to de-escalate the situation?

The simple answer is intra-EAC politics (which serve to accentuate the body’s resource constraints).

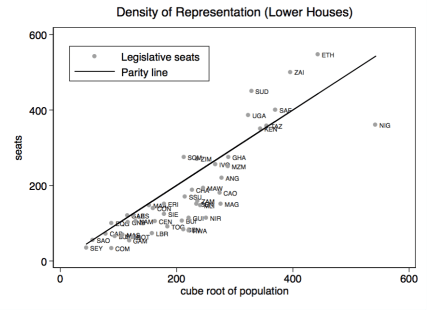

The EAC is a five-member (Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda) regional economic community (REC) that is arguably the most differentiated REC in Africa. Based in Arusha, Tanzania, it is a relatively robust institution replete with executive, legislative and judicial arms.

Like is the case for most African RECs, the EAC member states conceded precious little sovereignty to Arusha. For example, the EAC treaty does not directly empower the REC to intervene in a member country even in cases of gross violations of human rights (like is currently happening in Burundi). So far regional cooperation within the EAC has mainly focused on economic issues that do not pose substantial threats to sovereignty. It is for this reason that the EAC has avoided any kind of direct intervention in Burundi to end what is a singularly political crisis — both within Burundi and at the regional level.

That said, Article 123 of the EAC treaty provides a loophole for intervention.

The Article stipulates that the purpose of political cooperation among EAC member states is to, among other things: (i) strengthen the security of the Community and its Partner States in all ways; and (ii) preserve peace and strengthen international security among the Partner States and within the Community. In my view these clauses mandate the EAC to protect both the internal security of Burundi as well as intra-EAC security.

It is important to note that so far the norm has been to treat vagueness in African REC treaties as a call to inaction. But vagueness also provides willing interveners with a fair amount of latitude over interpretation. Furthermore, since 2000 the trend within African RECs has been to dilute the infamous OAU non-intervention clauses (see the AU treaty, for example) especially with regard to security matters.

It is not hard to see how the conflict in Burundi poses a clear and present danger to both Burundi’s internal security as well as peace and security within the EAC.

We know from history that an all out civil war in Burundi would threaten the security of the region. Burundi’s ethnic make up roughly mirrors that of Rwanda. Ethnic conflict in Burundi would inevitably elicit an intervention from Rwanda, thereby regionalizing the conflict (with an almost guaranteed knock on effect in eastern DRC). In addition, even though Kagame may not be a fan of Nkurunziza, he lacks the moral authority to criticize him given recent moves to scrap term limits in Rwanda.

If Rwanda (overtly) intervenes in Burundi, it is not clear which side Tanzania — a critical player — would take (especially because of the implications for the stability of eastern DRC). Kigali and Dodoma do not always see eye to eye. In addition, the new Tanzanian president, John Magufuli, is not particularly close to his Kenyan counterpart on account of his closeness to Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga. This may limit the possibility of collective action on Burundi by the EAC’s two leading powers.

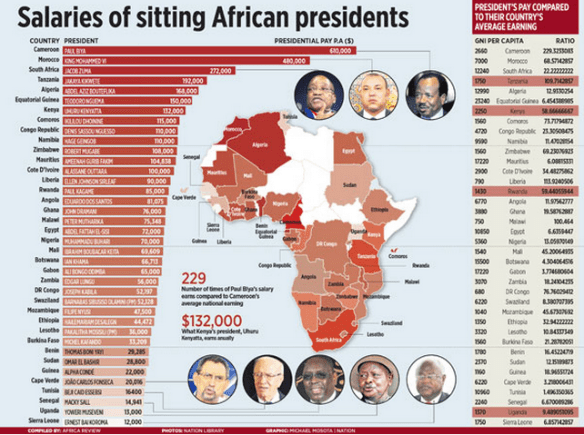

And then there is Uganda. President Yoweri Museveni is currently the designated mediator in the Burundian negotiation process. But he is currently preoccupied in his bid to win an nth term in office (who’s counting?) His legitimacy as a mediator is seriously in question on account of his political record back home. Recall that the proximate cause of the current crisis in Burundi was Nkurunziza’s decision to violate term limits. Museveni scrapped term limits in 2005 and has systematically squeezed the Ugandan opposition into submission through heavy handed tactics that are direct violations of human rights.

Sadly for Burundians, the current state of inter-state relations within the EAC is strongly biased against any robust intervention to stop the violence that is increasingly becoming routine. Nkurunziza knows this, and will likely try to make an end run on his perceived political opponents before the wider international community begins to pay closer attention.

Lastly, the other possible interveners — the UN and the EU — are also not likely to intervene in Burundi any time soon, despite the country’s heavy dependence on foreign aid. Europe is hobbled by the ongoing refugee crisis and the war on ISIS. As for the UN, it increasingly launders its interventions through region or sub-regional IOs (see for example AMISOM in Somalia, under the AU). This kind of strategy requires a willing regional partner, something that is lacking in the case of the EAC (or the AU for that matter).

In the next few weeks there will probably be attempts at mediation and calls for a ceasefire. But my hunch is that things are likely to get much worse in Burundi in the short term.

There are strong signs of ethnic violence. More than 300 people have been killed since President Pierre Nkurunziza successfully violated term limits to stay in office for a third term early this year. The ensuing violence has forced over 220,000 to flee the country, while scores remain displaced internally. Over the last week alone more than 80 people have been murdered in what is increasingly looking like a civil war rather than mere civil unrest met with heavy-handed repression.

There are strong signs of ethnic violence. More than 300 people have been killed since President Pierre Nkurunziza successfully violated term limits to stay in office for a third term early this year. The ensuing violence has forced over 220,000 to flee the country, while scores remain displaced internally. Over the last week alone more than 80 people have been murdered in what is increasingly looking like a civil war rather than mere civil unrest met with heavy-handed repression.