Last Saturday Nigeria’s electoral management body (INEC) postponed the February 14th national elections to March 28th. State elections were also moved from February 28th to April 11th. The official account is that INEC reached the decision after it became clear that the military would not guarantee security on election day (and therefore needed six weeks to pacify the northeast before reasonably peaceful elections could take place).

The head of INEC, Attahiru Jega, was categorical that “for matters under its control, INEC is substantially ready for the general elections as scheduled, despite discernible challenges being encountered with some of its processes like the collection of Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs) by registered members of the public.”

Naturally, the postponement raised a lot of questions.

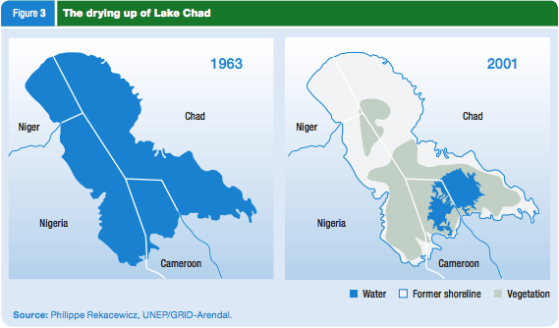

Boko Haram has been terrorizing Nigerians for the better part of six years. It is therefore a little odd that the military suddenly found the magic formula to quell the insurgency in exactly six weeks. Why now?

Reactions from several commentators questioned the intentions of the Nigerian military, and by extension, of the Goodluck Jonathan Administration.

- At the New Yorker Alexis Okeowo wonders why after six years the government has suddenly found the will and power to neutralize Boko Haram in six weeks. She argues that negative sectional politics prevented Jonathan, a southerner, from extinguishing the Boko Haram before the insurgency (mainly concentrated in the northeast) got out of hand. Okeowo also pours cold water on any hopes that a Buhari presidency would be any better for either Nigerian democracy or nation-building.

- Tolu Ogunlesi at FT invokes the events of 1993 – that saw Moshood Abiola robbed of the presidency after an election – in arguing that the postponement might, among other things, be a sign of both a resurgence of the Nigerian military and an attempt by the same to prevent Buhari (who is perceived to harbor intentions of reforming the military) from becoming president.

- Both Karen Attiah (Washington Post) and Todd Moss (CGD) see in the postponement a risky gamble by Jonathan and the military that might pay off (and result in a reasonably acceptable conduct of elections in six weeks) or completely backfire and mark the beginnings of a period of political instability in Nigeria.

- Alex Thurston over at Sahel Blog notes that while the Jonathan campaign has praised INEC’s decision, the Buhari camp has expressed “disappointment and frustration [with] this decision.” But at the same time Buhari urged all Nigerians not to take any actions that might further endanger the democratic process in the country. Whether the opposition will heed Buhari’s call will crucially depend on the outcome of the March 28th contest.

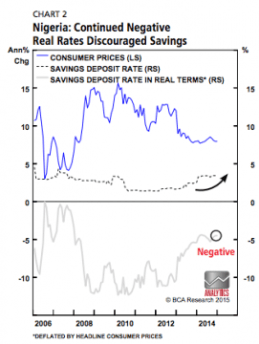

- Chimamanda Adichie, writing in the Atlantic, terms the postponement “a staggeringly self-serving act of contempt for Nigerians” that unnecessarily introduces even greater uncertainty into Nigeria’s political climate [ incidentally, following the postponement Nigeria’s overnight lending rate soared to 100 pct and the Naira hit 200 against the US dollar on Tuesday].

At face value, INEC’s decision seems reasonable. The security situation in the northeast makes it impossible to conduct a credible election. Plus, given Nigeria’s election law, it’s probably in the interest of the opposition candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, for elections to be conducted in the northeast (the winner needs a plurality of votes, and at least 25% in two thirds of the states and Abuja). The decision is also squarely constitutional. Like most Commonwealth states, election dates in Nigeria are not constitutionally fixed, and can be moved by the EMB. The only constraint on INEC is that elections must be head by April 29th, a month ahead of the constitutionally-mandated handover date of May 29th. Lastly, postponement buys INEC more time to issue permanent voter cards (PVCs). As of February 4th, only 44 out of 68.8 million potential voters had been issued with a PVC, a requirement to be able to vote (Lagos, a Buhari stronghold, had an issuance rate below 40%). These reasons might explain Buhari’s reluctant acceptance of the INEC decision.

That said, the timing of the postponement and the manner in which it was done are suspect. The Nigerian security establishment understood the challenge that Boko Haram posed with regard to the conduct of peaceful elections years in advance. So why act a week before the election? In addition, it was quite clear that the directive did not come from the generals per se, but from Aso Rock via the national security adviser Mr. Sambo Dasuki. The result is that the military has come off as an interested player in the election. At the same time, Mr. Dasuki’s involvement has dented (even if just slightly) INEC’s credibility as an independent arbiter in the process. As is shown below, Nigerians’ trust of the electoral process is already very low.

Confidence in the integrity of Nigerian elections

For the incumbent Goodluck Jonathan, the postponement presumably buys more time to try and dampen Buhari’s momentum. Some have argued that it also allows him to device ways of ensuring a victory, whether through clean means or not. My take on this is that this strategy will probably backfire. First, it signals to voters weakness and unfair play – things that might anger fence-sitters and make them break for Buhari come March 28th. Second, the election monitoring literature tells us that smart incumbents rig elections well in advance. This is for the simple reason that election day rigging (or rigging too close to the election) is often a recipe for disaster (see Kenya circa 2007).

These elections will be the closest in Nigeria’s history. The polls are essentially tied. The current postponement will no doubt raise the stakes even higher ahead of March 28th. Furthermore, the shenanigans of the past week will increase pressure on INEC to conduct clean elections, especially in the eyes of Buhari supporters.

Ultimately the folly of the postponement may be that it has raised the bar too high for INEC. Nigeria might find itself in a bad place if Buhari loses an election marred by chaos and irregularities.