This is from The Development Set:

Let’s pretend, for a moment, that you are a 22-year-old college student in Kampala, Uganda. You’re sitting in class and discreetly scrolling through Facebook on your phone. You see that there has been another mass shooting in America, this time in a place called San Bernardino. You’ve never heard of it. You’ve never been to America. But you’ve certainly heard a lot about gun violence in the U.S. It seems like a new mass shooting happens every week.

You wonder if you could go there and get stricter gun legislation passed. You’d be a hero to the American people, a problem-solver, a lifesaver. How hard could it be? Maybe there’s a fellowship for high-minded people like you to go to America after college and train as social entrepreneurs. You could start the nonprofit organization that ends mass shootings, maybe even win a humanitarian award by the time you are 30.

If you asked a 22-year-old American about gun control in this country, she would probably tell you that it’s a lot more complicated than taking some workshops on social entrepreneurship and starting a non-profit. She might tell her counterpart from Kampala about the intractable nature of our legislative branch, the long history of gun culture in this country and its passionate defenders, the complexity of mental illness and its treatment. She would perhaps mention the added complication of agitating for change as an outsider.

But if you ask that same 22-year-old American about some of the most pressing problems in a place like Uganda — rural hunger or girl’s secondary education or homophobia — she might see them as solvable. Maybe even easily solvable….

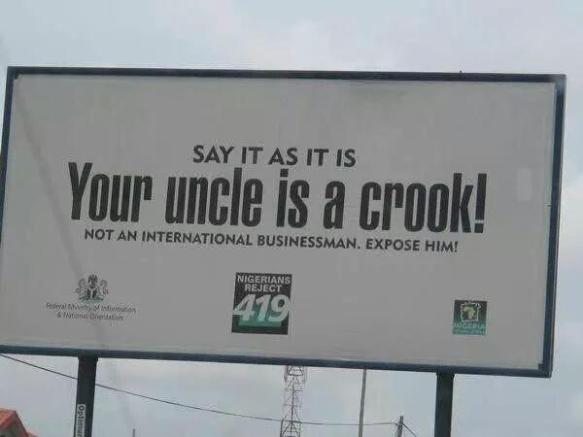

Part of what drives this belief in the easy solvability of other people’s problems is a tendency to view systemic political failures in developing countries as arising from the moral failures of leaders, or a general lack of knowledge. It is for this reason that otherwise intelligent and reasonable people are able to understand, for example, the political basis of legislative homophobia (or racism) in Alabama but not in Uganda. In the former case politicians are then allowed to “evolve” with the views of their electorates, while in the latter case they must be dragged to the moral high ground kicking and screaming (at the threat of foreign aid withdrawal).

This is not to suggest that “local politics” variables explain everything. Or that we should subordinate everything to local politics, especially in the face of despicable human rights abuses (as was the case with the offensive and dangerous Ugandan anti-gay law). Rather, it is a call for a balanced understanding of complex political actors (and their incentives) in the developing world.

The whole thing is worth reading, especially the bits about America’s own “unexotic underclass”:

…….. I think there is tremendous need and opportunity in the U.S. that goes unaddressed. There’s a social dimension to this: the “likes” one gets for being an international do-gooder might be greater than for, say, working on homelessness in Indianapolis. One seems glamorous, while the other reminds people of what they neglect while walking to work.

There is also a response here which argues against the false choice of helping the poor in America vs in the developing world.

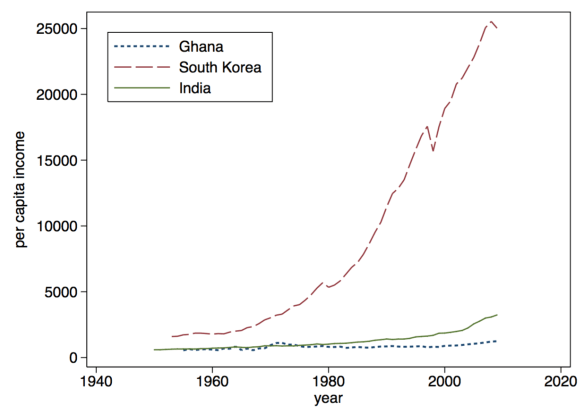

And by the way, despite having grown up in Nairobi, I only got interested in development after volunteering with Unite for Sight in Ghana.

Young South Africans are presently debating the merits of their country’s post-apartheid settlement. Many feel that in a rush to secure a stable political and economy transition the ANC leadership did not bargain hard enough for structural changes in South Africa’s political economy (

Young South Africans are presently debating the merits of their country’s post-apartheid settlement. Many feel that in a rush to secure a stable political and economy transition the ANC leadership did not bargain hard enough for structural changes in South Africa’s political economy ( Appearances at Chatham House, meetings with business leaders at home and abroad, and modest successes in Parliament further add to the emerging image of an insurgent party that knows the rules and can play by them (even if with a view of eventually changing the same rules).

Appearances at Chatham House, meetings with business leaders at home and abroad, and modest successes in Parliament further add to the emerging image of an insurgent party that knows the rules and can play by them (even if with a view of eventually changing the same rules).

This reflects several factors: the far higher remarriage rates among men following widowhood or divorce, the greater average life expectancy of women, and, in places, the ravages of HIV and conflict. As a result, one in 10 African women 15 and older are widows. And these women are much more likely to head their own households; 72% are heads of the family.

This reflects several factors: the far higher remarriage rates among men following widowhood or divorce, the greater average life expectancy of women, and, in places, the ravages of HIV and conflict. As a result, one in 10 African women 15 and older are widows. And these women are much more likely to head their own households; 72% are heads of the family.