This is a guest post by Grieve Chelwa, UCT Economics PhD and current Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for African Studies at Harvard University.

Here’s Ken Opalo’s reaction to Alex de Waal’s piece on the African academy. Recall that de Waal’s piece was critical of the absence of African scholars in producing scholarship on Africa.

As I read Ken’s piece, these 3 things immediately struck me:

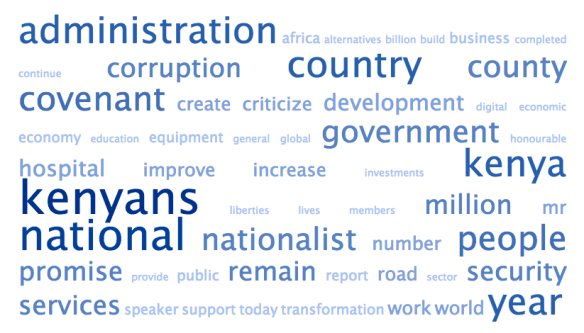

1. Ken says: “As a social scientist, my knowledge of Kenya is largely informed by my experience as a Nairobian. Over the years I have had to learn a lot about the rest of Kenya, in much the same way an Australian would. In doing so I incurred a lower cost than a hypothetical Australian would, for sure, but the cost was not zero. The point here is that it is not necessarily true that I have an innate ability to *know* Kenyan politics better than an Australian ever would if they invested the time and effort.”

Really, Ken? As an undergrad at the University of Zambia, I was always struck by the intimate knowledge my lecturers had of the country. The kind of knowledge outsiders could only pretend to have. Ken acknowledges that the costs of learning about Kenya differ between Kenyans and non-Kenyans – and this is precisely the point de Waal is making. Because outsiders face a higher cost, and combined with their academic privilege as gatekeepers of leading journals, the scholarship on Africa is consequently poorer than it should.

The longer Ken and I live away from “home” as we currently do, the more we become like this hypothetical Australian. I think de Waal isn’t speaking about us Ken. He’s speaking about that lady and gentleman who’ve spent a lifetime lecturing at the University of Nairobi, at the University of Zambia, at Ibadan, etc so that their costs of knowing and writing about their respective countries are now almost zero. Paradoxically, the voices of these fountains of wisdom are nowhere to be seen in the “leading” journals.

2. Ken then says: “And who is to say that I would necessarily be able to articulate a research agenda on whatever subject in Malawi better than a Southern Californian? What proportion of Kenyans can locate Bangui on a map?”

In my experience, African-based scholars, unlike their boisterous counterparts in the West, rarely pretend to be experts beyond their country of nationality. A lecturer at the University of Zambia spends most of their time thinking and writing about Zambian problems. On the other hand, it’s not unusual to see a Western scholar jumping from country to country in Africa pontificating on this or that. These are the types who describe themselves as “African Experts” on their curriculum vitaes. And by the way Ken, the typical Kenyan needn’t know where Bangui is (although I don’t doubt that they do). But the typical Kenyan academic certainly knows where Bangui is.

3. Lastly Ken says: “The problem is not that Western academics are asking the wrong questions, or that certain methodological approaches are privileged over others. The real problem is that there is a limited pool of high quality Africa-based scholars.”

Where is the evidence Ken for this often-heard (especially in the West) accusation that African scholars are low calibre? Without providing any evidence, all that you’re doing is discrediting the many teachers who’ve taught generations of African undergraduates at African universities over the years – some of these undergraduates have gone on to collect advanced degrees at some of the leading universities in the world.

The bigger problem here (and I think Godwin Murunga made this point on a thread on Nic Cheeseman‘s wall) is that African academics have given up on playing the academic arms race that’s infected the Western academy. In the same way Ken’s hypothetical Australian faces higher costs in learning about Kenya, African academics also face prohibitively higher costs in trying to publish in Western journals (they are not in the networks, desk rejected on the basis of institutional affiliation, clientelism, etc…). It’s tiring and they just don’t want to bother playing that tiring game.

Two quick reactions:

[i]. There is a lot of bad quant research on Africa out there done by fly-by-night “Africa experts” (I am talking lots and lots of silly experiments and cross-country regressions). But there is also a lot of great work that is bringing hard data (both micro and macro) to bear in answering important questions in a variety of fields. To the extent that we all acknowledge that making African states legible, through data, improves the quality of governance, then we should encourage more aspiring African scholars to acquire the tools needed to study their respective states and societies. And as a comparativist, I think that there is value in cross-country comparisons. A Zambian scholar who has studied Kenya probably gets Zambia better than one who ONLY studies Zambia. I don’t think it is wise for African academics of give up on the “tech arms race.” A diversity of skills and methodologies is good for overall knowledge production. I firmly believe that the credibility revolution in social science has left us all unambiguously better off.

[ii]. I also don’t think that pointing out the dearth of high quality research in African universities is a controversial claim. We can quibble over the politics of university rankings, the privileging of specific forms of “evidence”, et cetera, but the fact is that Africa, as a region, has very few top notch universities. This is not to say that there aren’t any centres of excellence in Nairobi, Lusaka, Cape Town, or Ibadan. My own experience tells me that a variety of factors — poor pay, insane teaching loads, consultancies, etc — make it very difficult for Africa-based academics to do research (or for that matter, to teach well). Only focusing on demand side issues without addressing the supply side ignores the basic challenge of how to improve the conduct of research in African universities. My point here is that even if we fixed the biases at leading journals Africa-based scholars would still be handicapped relative to their counterparts based in the West. These specific supply side issues matter.

Of course, underlying all this discussion is a politics of knowledge production. We live in an uncomfortable world in which scholarship on Africa by Africans is hard to come by in Western universities; and Western “experts” tend to have privileged access to policymakers on the Continent relative to Africa-based researchers. My contention is that solving this problem requires both demand and supply side solutions. Of course we should encourage Western academics to read, cite, and teach more works by Africans. And of course African governments should take their own scholars more seriously. But only focusing on the demand side problems ignores serious supply side constraints that are faced by Africa-based scholars.