Dar es Salaam is a pleasant town in late June. I had only been there once before, back in 2011 when I stayed for a day and a half to catch the Tazara. I didn’t like it then because of the heat and humidity (humidity is up there with cats – I am allergic – on the list of things I cannot stand). But this time round it was nice, I managed to walk around town marveling at the pillars of concrete and glass that are rising up in every corner of the city. The construction boom puts even Nairobi to shame, enough to make me think that the suggestions that Tanzania may soon eclipse Kenya as the place where all the action is in East Africa are not that far fetched after all (see image and this piece).

My only complaint was that a prime section of the beach front still remains under-utilized, although this might be because of the presidential palace nearby. I hear you can’t drive there at certain times of the day (Stop channeling Mugabe, Bwana Kikwete. Also, let Chadema be). Oh, and I did manage to drive on the Kibaki road. I thought it was a new road, but it is not. Sections of it are actually pretty bad. Apparently, the Tanzanian government is planning an upgrade soon. I also drove past Mwalimu Nyerere’s home. It made me respect the man even more.

I arrived in Dar late on Tuesday night after many hours of travel by bus. On Thursday morning I was scheduled to continue with the second leg of the journey to Lusaka. I was at the bus stop by 5:45 AM, still sleepy. I had stayed up late the previous night, watching the Confederation Cup matches of the day, reading and writing my Saturday column. I fell asleep as soon as I got to my seat.

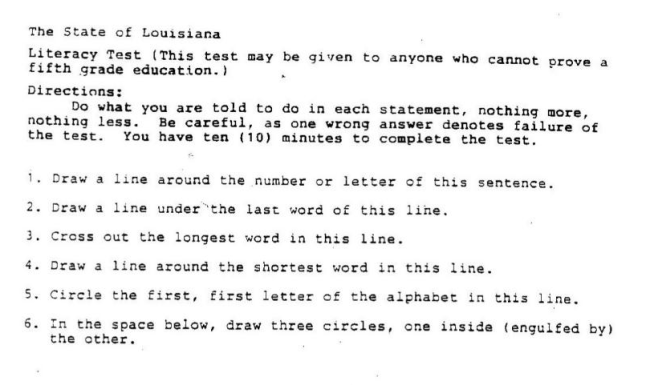

Dar’s public housing units. For a moment I thought that the choice of color was meant to discourage applicants. Until I saw the pink public housing headquarters. Some of the units are in really nice parts of town.

The bus left the station promptly at 6:15 AM. Tanzania is huge. From Dar es Salaam to the Tunduma border is about 931 kilometres. The drive to the Zambian border took a total of 16 hours.

As I said in the previous post on this trip, I regretted taking the bus. If you want to travel overland between Dar and Lusaka, take the train. It is a million times more pleasant. There is a restaurant and a bar (that serves Tusker) on the train. There are bathrooms. And you have a bed. Plus the train is just slow enough that you can read and truly appreciate the empty Tanzanian countryside.

But the trip wasn’t all gloomy. The scenery was still enjoyable. Sections of Tanzania are quite hilly, with amazing views of cliffs and rivers and rock formations. At some point past Iringa I saw what seemed to be the biggest tree plantation in the world. For miles and miles all I could see were rows and rows of trees. And when there were no trees there were rows and rows of sisal. Someone is making bank off the land in that part of the country.

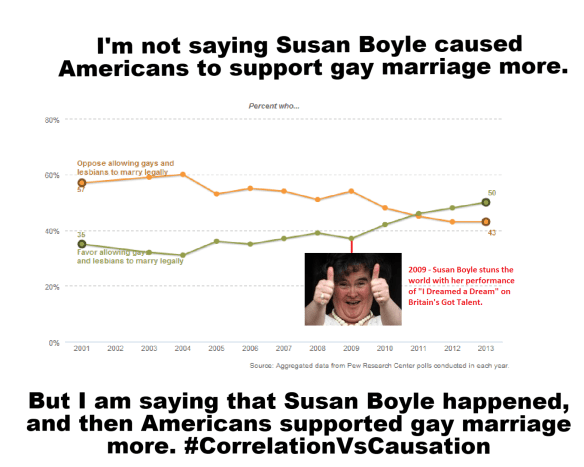

Also, western Tanzania is a lesson on how hard it is to achieve economic development in the context of a sparsely populated country. Such situations make it impossible to reach everyone with the grid and water pipes. Either the government has to wait for demographics to work its magic (again, see figure above – and be sure to check out this story on the Africa-driven demographic future of the world) or provide smart incentives to accelerate the process of urbanization.

For those who went to high school in Kenya, journeying by land through Tanzania reminded me of Ken Walibora’s Siku Njema. I felt like I was retracing the steps of Kongowea Mswahili. Some day I would like to go back and spend some time in Morogoro and Iringa. By the way, Siku Njema is by far the best Swahili novel I have ever read (which reminds me that it has been eight years since I read a Swahili novel. Suggestions are welcome, preferably by Tanzanian authors). It is about time someone translated it into English for a wider audience.

We reached Tunduma some minutes past 10 PM. The border crossing to Nakonde on the Zambian side was closed. Some passengers on the bus left to rent out rooms for the night. I decided to tough it out on the bus with the crew and a few other guys. Desperate for something warm to eat, I had chicken soup and plain rice for dinner. The “restaurant” reminded me of the place in Tamale, Ghana where Vanessa and I got food poisoning two months earlier. But I was desperate. I quickly ate my hot soup and rice and hoped for the best.

I crossed the border early in the morning on foot. The bus had to wait in line for inspection and to pay duty for its cargo (It is at this point that I learned that the bus was actually going all the way to Harare in Zimbabwe). I am usually very careful with money changers, but perhaps because of my tiredness and lack of sleep the chaps in Nakonde got me.

I crossed the border early in the morning on foot. The bus had to wait in line for inspection and to pay duty for its cargo (It is at this point that I learned that the bus was actually going all the way to Harare in Zimbabwe). I am usually very careful with money changers, but perhaps because of my tiredness and lack of sleep the chaps in Nakonde got me.

If you ever cross to Nakonde on foot wait until you are on the Zambian side to exchange cash at the several legit forex stores that line the streets.

The bus finally got past customs at noon (on Friday). In Nakonde we waited for another two hours for more passengers and cargo.

I took the time to get some food supplies. Lusaka was another 1019 kilometres away.

By this time I was dying to have a hot shower and be able to sleep in a warm bed. It was cold. Like serious cold. And Lusaka was still another 14 hours away.

I slept lightly through most of the 14 odd hours. In between I chatted with two Kenyan guys that were apparently immigrating to South Africa, with little more than their two bags. They said that this was their second attempt. The previous time they found work in Lusaka and decided to stay for a bit before going back to Nairobi. They were part of the bulk of passengers from Nakonde who were going all the way to Harare. Apparently, this is the route of choice for those who immigrate from eastern and central Africa into South Africa in search of greener pastures.

Before it got dark we saw several overturned trucks on the road. I slept very lightly, always waking up in a panic every time the driver braked or swerved while overtaking a truck just in time to avoid oncoming traffic. My only source of comfort was the fact that the driver was a middle aged man, most likely with a family to take care of and therefore with a modicum of risk aversion.

I arrived in Lusaka at around 4 AM, more than three days and 2871 kilometres since leaving Nairobi.

I said goodbye to my two Kenyan countrymen and rushed out of the bus as soon as I could. On the way to my hotel I couldn’t stop thinking how much I would like to read an ethnography of the crew of the bus companies (and their passengers and cargo) that do the Dar to Harare route.

At Lusaka Hotel that morning I had the best shower I had had in a very long time. And slept well past check out time. I had two months of fieldwork and travel in Zambia to look forward to.