Financial Times reporting on the creation of the Kenya Colony

Kenya is 55 today. Or 98 if you take the Order in Council of July 1920 creating the Kenya Colony to be the founding instance of the geographical entity that became Kenya (well, most of its land anyway. The coastal strip was then still a property of the Sultan of Zanzibar). I would actually suggest a different date, 1907, to be the instance when the Kenyan state opened shop. This is when the first rudimentary legislature was established (in Nairobi) within the East African Protectorate, thereby enabling settlers, and by extension indigenous Kenyans, a little more say on government policy. Yes, you are very right in thinking that this view has nothing to do with the fact that I am writing my dissertation on African legislatures.

Direct representation came in 1944 with Eliud Mathu, but settler demands brought to the fore issues of the welfare of indigenous Kenyans as well. It was unlike the IBEAC days when the locals had almost no say at all. Speaking of the IBEAC, you could make the argument that Kenya is actually 118 – going by the date, 1895, when IBEAC officially handed over the managed of British East Africa to the Foreign Office.

Anyway, since much of the period between 1895 and 1963 was marked by the exclusion of the vast majority of indigenous Kenyans form the political process let’s take 1963 as the starting point. However, the significance of the other dates shouldn’t be lost on us. Kenyan history did not begin in 1895 or at midnight on December 12th 1963. This account will be brief. Feel free to add to it in the comments section.

Independence in 1963 came on the heels of a brief period of partial self-government. Official history taught in schools puts President Jomo Kenyatta as the first indigenous leader of government. Most Kenyans don’t know that Ronald Ngala was official leader of government business in the LEGCO and even became Chief Minister. At the time Kenyatta was in prison, KANU had just won elections but refused to form a government until Kenyatta was released from prison. Back in 1958 Jaramogi Oginga Odinga had adamantly insisted in the LEGCO that “Kenyatta Tosha” [my own rendition] and that a precondition for independence and self government was the release of Kenyatta from prison.

Kenyatta with Odinga and Mboya

When Kenyatta was released from prison he found two dominant parties, KADU and KANU. Both tried to persuade him to be their chairman since it was clear that whoever had Kenyatta on their side would win the independence elections (Daniel arap Moi, a KADU man, had even visited Kenyatta in Kapenguria). Because of interests (especially around land; KADU was then perceived as a tool of the settler community) and historical reasons (James Gichuru, a KAU man, was a founder member of KANU) Kenyatta chose KANU over KADU. At independence he inherited a state that was dominated by the Civil Service and Provincial Administration. Kenyatta kept this intact. Sons of collaborators who hunted down the Mau Mau inherited the colonial state. Unlike in many African countries where independence brought about a steep discontinuity – think about Guinea, for instance – in Kenya there was a good amount of continuity.

It was almost as if the Ashanti aristocracy and colonial era collaborators had inherited the reigns of power in the Gold Coast in 1957 and not the outsider mass mobilizer, Kwame Nkrumah; Or the Kabaka, instead of Obote, had inherited power in Uganda in 1962.

The nature of colonial transition explains Kenya’s political stability and reasonable economic success since independence (at least compared to its African peers). It is Sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest non-mineral economy and has never experienced a successful military coup (though attempts were made in 1971 and 1982).

Kenya is a lesson on the difference state capacity can make. Any attempts at separatist armed struggle – from the Shifta War, to the Sabaot Land Defense Force, to the Mombasa Republican Council – have been crushed (sometimes with foreign help). Civilian insecurity is a serious problem that is getting worse. But the state is not one that can be toppled by bands of armed men on technicals (see here (pdf) for reasons as to why).

The country got a stable start (and many may argue normatively unjust system) because the indigenous upper class inherited the economy and a strong and moderately developed state (largely because of the need to defeat the Mau Mau insurgency) almost intact. Individuals close to Kenyatta took over settler farms almost intact. The last British Officer in the Kenyan military left in the 1970s. The social foundation of the state ensured continuity (redistribution of land to the masses was a non-starter) and the inherited strong bureaucratic-state had the capacity to suppress any form of dissent (of course starting with ex-Mau Mau freedom fighters who demanded for a greater degree of land redistribution). It also helped that Kenyatta and his close associates were from Central Kenya, the economic heart of the country.

Snapshot of the triumph of conservatism: Kenya’s Four Presidents, Kenyatta I, Kenyatta II, Kibaki and Moi

The confluence of economic and political power (in Kenyatta and his close co-ethnics) made redistributive policies unworkable. As Bates has ably argued, this explains the great investments that the Kenyan state made in agriculture. This also explains why Kenya never flirted with socialism, unlike nearly all of its African (Ghana again being a good example) peers. Leftist elements within KANU lost out in 1966.

Even among the Kenyan public, the idea of individual ownership of property – and especially land – had become accepted as sacrosanct. Many had come to a pragmatic acceptance of inequality as a feature of life. It was OK for the big men to appropriate thousands of acres of land as long as ordinary families got a few acres for their own use. Right from the beginning, prevailing socio-economic conditions and the attitudes of politically relevant groups made it easy for the conservative ruling class to pursue right of center economic policies. There was no land revolution in the 1960s.

When Kenyatta died in 1978 a lot of things had gone wrong. Many freedom fighters had been neglected by the very people who collaborated with the colonial administration and who now had control over the state. Negative ethnicity had irredeemably corrupted the state and made Kenyatta’s co-ethnic unwilling to share state power or wealth with non co-ethnics. Pio Gama Pinto, an active backbencher in Parliament was assassinated in 1965. Tom Mboya, a charismatic likely successor to Kenyatta was assassinated in 1969. Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, a populist co-ethnic of the president who advocated for more redistributive policies, was also assassinated in 1975. The main opposition party had been banned in 1969. A raft of constitutional amendments had destroyed the regionalist structure of the Kenyan government and centralized power in the hands of the president.

But even at the most trying of times, twice in 1969 (the assassination of Mboya, the riots in Kisumu during a Kenyatta visit and the subsequent banning of the main opposition party KPU) and again in 1975 (following the murder of J. M. Kariuki), the Kenyan state held strong. Order was restored. For better or worse conservatism triumphed over populism and radicalism.

Moi’s succession brought new hope; like all good future dictators he started off by releasing political prisoners of his predecessor. But his security of tenure was never a given. He barely survived attempts to exclude him from succeeding the president as required by law. My own reading of the situation is that a key factor in the lawful succession in August 1978 was Charles Njonjo, the unashamedly Anglophile son of a colonial era chief from Kabete (some call him Sir Charles, others the Duke of Kabeteshire). As the Attorney General Njonjo probably eyed the presidency. Yet he wanted to get there lawfully. Moi was his way of outfoxing the Mungai-Koinange. Njonjo, like all good Kenyans, had internalized whatAtieno-Odhiambo calls the country’s pervasive “ideology of order.” Moi probably knew this. And the fact that there was an intra-Kikuyu split along the flow of River Chania. The Kenyatta presidency was a mostly Kiambu affair. Nyeri Kikuyu (who bore the brunt of the Mau Mau insurgency and counterinsurgency were largely excluded). Moi appointed a Nyeri man, Mwai Kibaki as Vice President. For good measure, he kept Njonjo – well until he got rid of him in 1985.

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, a man that many in Kenyatta’s inner circle had viewed as a passing cloud, then went on to rule Kenya for 24 years. As an outsider his rule was marked by redistribution (as in the District Focus for Rural Development, gated); an attempt at greater control of the political sphere (he turned Kenya into a party-state); and poor economic performance (Kenya’s dominant economic group was excluded from political power). The coup attempt in 1982 was a reaction to Moi’s controlling tendencies. Earlier in the year he had engineered a change in the constitution to make Kenya a one party state. By 1990 a combination of economic collapse and increasing popular resentment made political liberalization inevitable (it also helped that democracy promotion by Western governments became sexy).

The most high profile political assassination during Moi’s rule was that of Robert Ouko in February 1990. Initially the government tried to suggest that the Foreign Minister committed suicide by shooting himself in the head, breaking his legs, and setting himself on fire. He then somehow found himself atop Got Alila where his remains were recovered by a herds-boy. Like all the high profile political assassinations before it, it is not clear whether this was a result of intra-palace rivalry or whether it was conducted on the orders of the Big Man.

Despite his many faults, Moi maintained the hold of the center. He saved the elite around Kenyatta from self-destructing by refusing to share power and wealth. More crucially, under Moi order continued to be a key pursuit of the state. In other words Kenya did not fall apart under the pressure of demands for political reform like most of its African peers did.

Multipartyism was reintroduced and elections held in 1992. Moi survived with 36% of the vote. The opposition was divided. Their only victory was getting Moi to concede to term limits. Worst case scenario the man would only be in power until 2002.

Moi retired after the 2002 election. In that year Mwai Kibaki won in a landslide, defeating current President Uhuru Kenyatta. The Kibaki presidency brought success and decline in equal measure. The economic consequences of the Kibaki presidency were largely positive. Kenyans acquired greater freedoms. It became OK to hurl abuses at the head of state without risking torture. The 2010 Constitution was enacted under Kibaki. But it is also under Kibaki that the country almost descended into civil war in 2007-08 following the rigged 2007 elections. Corruption and the ethnicization of state administration continued unabated. The euphoria and hope for genuine reform that marked the 2002 transition varnished. Earlier this year Kibaki retired to be succeeded by Uhuru Kenyatta, effectively bringing to power a significant portion of the group that lost the 2002 presidential election.

Moi retired after the 2002 election. In that year Mwai Kibaki won in a landslide, defeating current President Uhuru Kenyatta. The Kibaki presidency brought success and decline in equal measure. The economic consequences of the Kibaki presidency were largely positive. Kenyans acquired greater freedoms. It became OK to hurl abuses at the head of state without risking torture. The 2010 Constitution was enacted under Kibaki. But it is also under Kibaki that the country almost descended into civil war in 2007-08 following the rigged 2007 elections. Corruption and the ethnicization of state administration continued unabated. The euphoria and hope for genuine reform that marked the 2002 transition varnished. Earlier this year Kibaki retired to be succeeded by Uhuru Kenyatta, effectively bringing to power a significant portion of the group that lost the 2002 presidential election.

Moi was Kenyatta’s vice president, Kibaki was Moi’s vice president. President Uhuru Kenyatta is the son Kenya’s founding father.

As is implied by this account, the political history of Kenya has tended to revolve around key personalities, and the presidency. One defining characteristic of the Kenyan saga is the invariable triumph of conservatism over radicalism and progressivism. Great progressives from Pinto to Jean-Marie Seroney to Oginga Odinga, to Bildad Kaggia to J. M. Kariuki to Raila Odinga, to Wangari Maathai have fought hard and long to improve the lives of ordinary Kenyans. But the empire always strikes back. And wins. The Kenyan story is one of the triumph of conservatism over progressivism.

Indeed, most progressives eventually get swallowed up by the system.

Moving forward, it will be interesting to see how the new institutions created by the 2010 Constitution evolve. The Kenyan legislature is strong and continues to evolve (be sure to read my dissertation and book on this); the system of county governments will definitely chip away at the hitherto cohesive bureaucratic-administrative state; and the desire for rapid development and the management of economic equality will raise new problems of the conservative core of the Kenyan state. Will the centre continue to hold? Will Kenya continue to be economically center-right despite freer elections?

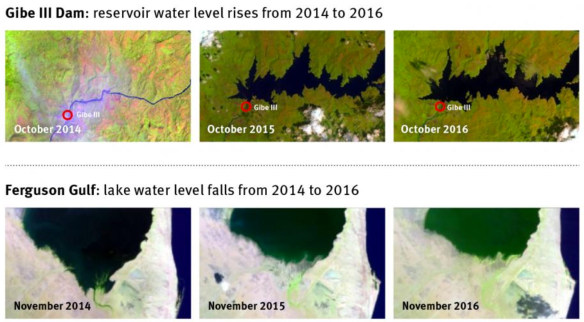

According to Sean Avery

According to Sean Avery At this juncture you may ask, why isn’t the Kenyan government up in arms over the Gibe projects?

At this juncture you may ask, why isn’t the Kenyan government up in arms over the Gibe projects?