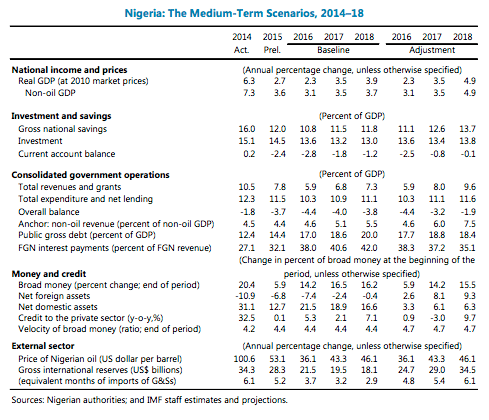

These are figures from an IMF Article IV country report in April of this year:

The one thing that jumped at me from this table was how little(as a share of total national output) the Nigerian public sector spends. The government barely takes in 10% of GDP in revenues; and spends between 11-12%. Also, for a country at its level of development (and with an economy of its size), Nigeria is weirdly debt free (relatively speaking).

You may be thinking that these figures must exclude state government expenditures — and you are wrong. The 11-12% figure is inclusive of state government expenditures.

In my view, this is a PFM smoking gun on the distortionary effects of oil dependence. Nigerian policymakers appear to be sated with the little revenue they are consuming (as a share of GDP) from the oil sector.

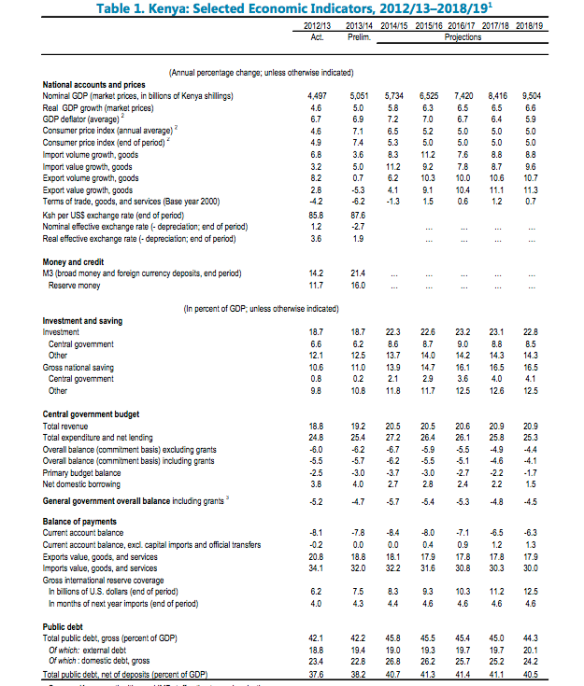

For a comparative perspective, take a look at Kenya’s numbers:

The Kenyan government gobbles up about a fifth of GDP in revenues, and spends about a quarter. The Nigerian government only takes in a tenth of GPD and spends just a little over a tenth. In addition, the Kenyan government’s debt/GDP ratio is twice Nigeria’s.

General government spending as a share of GDP within the OECD ranges from 33.7% in Switzerland to 58.1 in Finland. The OCED debt/GDP ratio average is 90%.

Back in grad school I took Avner Greif’s economic history class in which he emphasized the importance of organizations for economic development. Societies, big and small, organize out of poverty — by building and maintaining socially-attuned institutions that lower transaction costs. The scope and intensity of organizational capacity therefore matters for economic development (For more see here). It takes a well ordered state.

And from these two tables, it is fair to say that the Nigerian state is underperforming relative to its organizational potential. Perhaps it’s time more people in Abuja started reading Alexander Gerschenkron (however dated this might be).

The government picked Mr. Safa’s company, Privinvest, to supply ships, including patrol and surveillance vessels, and asked its help getting financing. The company disputes the characterization of the ships as military, saying they weren’t outfitted with weapons. Privinvest approached Credit Suisse about a loan for Mozambique, and a committee of senior executives, including then-CEO Gaël de Boissard, approved the deal.

The government picked Mr. Safa’s company, Privinvest, to supply ships, including patrol and surveillance vessels, and asked its help getting financing. The company disputes the characterization of the ships as military, saying they weren’t outfitted with weapons. Privinvest approached Credit Suisse about a loan for Mozambique, and a committee of senior executives, including then-CEO Gaël de Boissard, approved the deal.